innovation

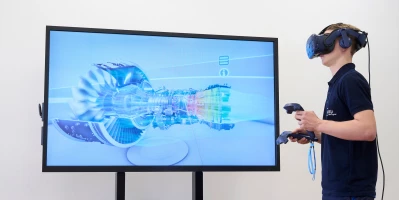

Industry 4.0 in aviation

Smart manufacturing in the aviation industry.

05.2016 | author: Silke Hansen | 7 mins reading time

author:

Silke Hansen

writes for AEROREPORT as a freelance journalist. For over ten years, she has covered the world of aviation focusing on technology, innovation and the market. Corporate responsibility reporting is another of her specialty areas.

Everybody’s talking about it—the Germans, the Americans and even the Chinese. In Germany they call it industry 4.0, in English-speaking countries they call it connected industry or the internet of things. For the aviation industry, it spells change as well. But what exactly is it?

“It’s actually quite hard to define connected industry since the term has been used in such a widespread and often highly vague manner. Suddenly everything is tagged 4.0—work, logistics, everything,” explains Tobias Strölin from the Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Engineering IAO in Stuttgart. Strölin prefers to talk of a “digitalization of value creation” and advises that “each company must define connected industry for itself.” Already ubiquitous in our personal lives, the internet is coming to manufacturing. Our economies and societies are becoming more and more digitalized, and that is changing the way we work and the way we manufacture. In the future, experts expect that people, machines, plants, logistics and products will be able to connect with one another in real time. Production will become largely autonomous—flexible, efficient and in line with the desires of the individual customer. The result is the smart factory, the textbook example of connected industry.

That this is possible in the first place is thanks to the latest information technology and new capabilities when it comes to processing data: increased storage capacity, higher speeds, a more compact size and better sensors. Meanwhile, huge advances in artificial intelligence have meant that lightweight robots are now available on the market for a comparatively reasonable price.

The basis of the forward-looking internet of things is technology that relies on what are known as cyber-physical systems, in which products and the means of production can communicate with one another and be connected together in a flexible way. “It’s like giving a component legs,” says Strölin. Using RFID technology based on electromagnetic fields, the component is able to identify itself and how it is to be processed, and make contact with the production facility. This facility then autonomously decides what is to be done and in what order. After the steam engine, assembly line, electronics and IT, could this really be the new fourth industrial revolution? A vision of the future?

Automated loading In blisk production, the machine adapts itself to the component it is about to process.

Automated loading In blisk production, the machine adapts itself to the component it is about to process.

Better than the human eye The quality assurance processes in the blisk manufacturing facility are supported by computer-controlled optical measuring systems.

Better than the human eye The quality assurance processes in the blisk manufacturing facility are supported by computer-controlled optical measuring systems.

Aviation plays by its own rules

“We in the aviation industry are still at the beginning of the road to connected industry. At the MTU location in Munich, we have operated two partially automated assembly lines for a number of years now, and we’re taking that a step further with our largely autonomous, digitalized blisk production center,” says Richard Maier, head of production development at engine manufacturer MTU Aero Engines. Other sectors such as the automotive industry are already at a more advanced stage. Even so, taken as a whole, the digitalization of industrial production is still in its infancy; aside from a few specific applications, the first demonstrators, or demo-labs, open their doors at universities and research institutes. “In five years’ time, at the end of the testing phase, we expect to see the first competitive advantages, followed by the first smart factories in ten to twenty years’ time,” calculates Strölin.

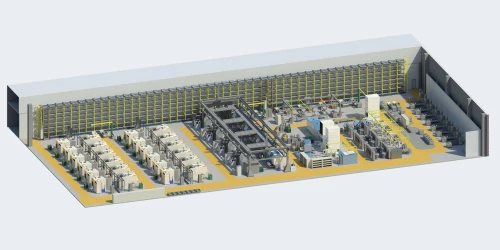

Nevertheless, manufacturing in the aviation industry operates by its own rules, and the smart factory concept is limited in terms of its transferability to this sector. To compare, Airbus produces 2.5 aircraft a day—while an automotive manufacturer can produce several thousand vehicles. “It’s still series production, but in far smaller quantities. It’s a far cry from mass production,” says Maier. He also points out that the technical demands placed on individual components are increasing all the time—meaning more and more processes to be executed, preferably in as integrated a manner as possible. As products become more complex, manufacturing them becomes harder. Stable processes are critical, says Maier. In the aviation industry, a lot is still done by individual manufacture. “We can’t just automate at any price,” says Maier. Nevertheless, automation in engine production is becoming increasingly worthwhile with the introduction of new families of components. This means applying a family concept to a core engine so that it can be scaled for multiple applications. The best example of this is the new PW1000G PurePower® Geared Turbofan™ engine family, which caters to five aircraft manufacturers and their model ranges. As a result, parts are highly comparable and can be manufactured in high volumes. MTU Aero Engines itself manufactures compressor blisks one of the company’s special areas of expertise for the PW1000G family. These high-tech components, compressor stages produced in a single piece, are manufactured in a newly built production hall that features a high level of automation and a smart management system. It is the world’s most up-to-date production facility for engine components of this type.

Automated blisk production

Blisks for the Pratt & Whitney GTF™ Engine Family are produced in a new and highly automated manufacturing hall. To the interaction ...

Digitalization as a catalyst

“There’s a great deal of potential for the aviation industry,” says Maier about connected industry. The sector must remain competitive in the face of cost pressure, particularly in high-wage countries. Tom Enders, CEO of the Airbus Group, which has production locations in France and Germany, is calling for the industry “to make use of the opportunities of the digital revolution. That means ensuring that the design, development and manufacture of our products become significantly faster and more efficient as well.” The European aircraft manufacturer is working on a factory of the future, in which it tests new manufacturing techniques and integrates them step by step: virtual development worlds for new aircraft, advanced digital technologies for the shop floor, a new generation of robots that works alongside people on the assembly line as well as additive manufacturing. Airbus is picking up the tempo. In its factory of the future, the assembly line will see the greatest increase in automation, where smart robots execute strenuous or repetitive tasks. In 2015, Airbus delivered 635 aircraft a new record. The company’s order books are full to bursting and it is setting its sights on increasing its production rates still further—up to 60 aircraft a month for its bestseller, the A320neo.

“Connected industry provides the foundation for a systematic learning process. It’s about learning from data and continuously optimizing processes. The internet of things will help us make complex processes more manageable—and that applies to the aviation industry as well,” says Dr.-Ing Christina Reuter from the Department of Production Engineering at RWTH Aachen University. According to the predictions of a Europe-wide study conducted on behalf of the Federation of German Industry, the digitalization of aerospace engineering will contribute ten billion euros a year of gross added value from 2025 onwards. It estimates that the industry will experience a digital revolution as part of a third wave—following the first waves in the automotive industry and logistics business.

Done, and on to the next one Finished components are automatically collected from the machine, which can then immediately start work on the next workpiece.

Interview with Tobias Strölin, Fraunhofer Institute

Mr. Strölin from the Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Engineering IAO provides his opinion on the topic: Are tablets finding their way into manufacturing?

In the eyes of the experts, the hurdles for the aviation industry are more regulatory than they are technical. Increased connectivity means a higher risk of cyber attacks—something to which the aerospace industry, with its extremely stringent security regulations, is particularly sensitive. All the same, IT security is the big challenge for all connected industry applications. Cars that drive themselves have long been technologically feasible, but while they do reduce the risk of accident, they bring new risks with regard to data security. “We have to find a reliable way to protect data from unqualified or unauthorized access,” agrees Maier.

While there are still hurdles to be overcome, Strölin remains confident. “In ten years’ time, we won’t even be talking about it, as digitalization will be here.” We can expect the gain to be considerable: according to calculations by McKinsey, factories stand to benefit the most from smart connectivity in an internet of things—up to 3.7 billion dollars of added economic value worldwide in 2025.