good-to-know

Clarity is everything: Key abbreviations in aviation

Bravo Alpha Two Eight Four. There is no room for the slightest misunderstanding in operations involving flying aircraft, which is why aviation has its own special system of communication.

author: Thorsten Rienth | 4 mins reading time published on: 06.08.2020

author:

Thorsten Rienth

writes as a freelance journalist for AEROREPORT. In addition to the aerospace industry, his technical writing focuses on rail traffic and the transportation industry.

If you look out the window on the approach to Geneva Airport, you can catch a glimpse of the number and letter combinations on the neighboring runway. Depending on the runway and direction of approach, you’ll see a large white “04”, “22”, “04L” or “22R” painted on the gray tarmac.

They represent the bearing of the runway the aircraft is approaching on in relation to the North Magnetic Pole. A runway pointing directly south gets an “18”, which corresponds to 180 degrees on a compass. This covers the range between 175 and 184 degrees. If the runway is pointing in the opposite direction, i.e. north, it will be at 360 degrees and labeled with a “36”. By the same logic, runway 22 in Geneva points roughly southwest. On parallel runways, the “L” and “R” stand for left and right, as you might expect. If there are three runways all pointing in the same direction, as you find at major airports like Frankfurt or Chicago, the middle one is given the suffix “C” for center.

No superfluous syllables

Abbreviations like these are common in every facet of aviation, where the highest possible level of precision and unambiguity in the language used is absolutely essential. That is especially true for the communications between the cockpit and air traffic control, or ATC for short. Any superfluous syllable, number or series of letters could lead to potential misunderstandings. So the command “reduce to minimum” doesn’t apply just to altitude and speed when an aircraft is on approach, but to the whole way aviation phraseology is developed.

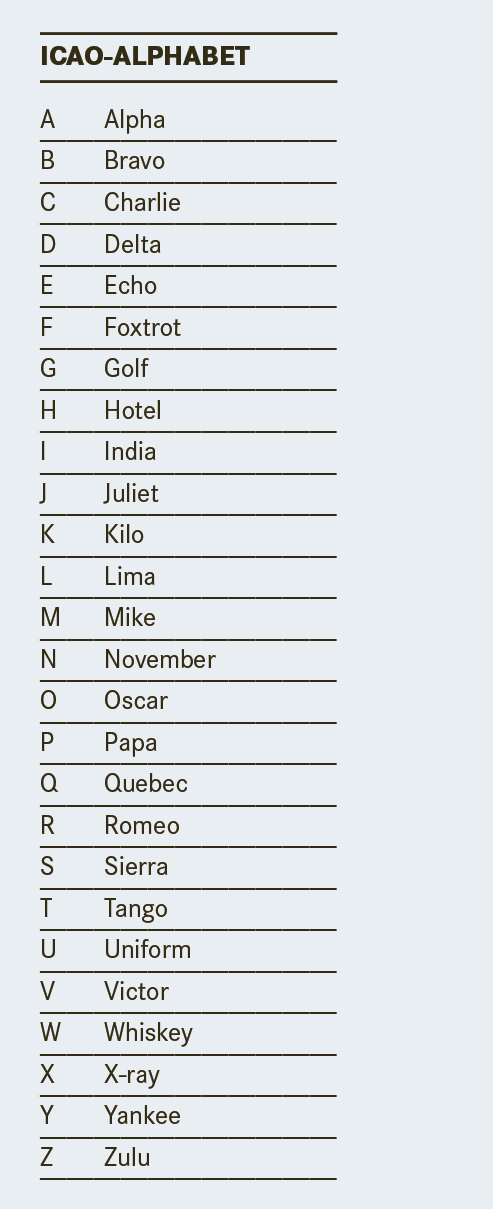

Aviation language is based on the alphabet of the International Civil Aviation Organization – the ICAO alphabet. While it’s easy to mix up the letters “M” and “N” through headphones when there is crackling and interference in the background, confusing “Mike” and “November” far less likely. In pilot lingo, flight “BA 284” from San Francisco to London becomes “Bravo Alpha Two Eight Four”.

If this flight is to keep its slot for takeoff based on the calculated takeoff time (CTOT in aviation-speak), the pilot must request clearance to taxi from the ATC tower in good time. Toward runway 28R, for example. The answer from the tower might be as follows: “Bravo Alpha Two Eight Four heavy taxi to runway 28R via Alpha, Quebec, Bravo, Foxtrot, hold short of 01Lima”.

“Heavy” refers to the Boeing 787-9 Dreamliner, the aircraft operating the flight, indicating a takeoff weight of more than 300,000 pounds. Alpha, Quebec, Bravo and Foxtrot signal the way across the apron. Next comes the instruction to wait up ahead of runway 01L, which crosses runway 28R. It is in that direction that BA 284 will taxi to next.

What sounds like secret code is really only pared-down command language: “rotate”, “positive climb”, “gear up”. The weather might be described as CAVOK: “clouds and visibility OK”.

In addition to normal radio communication systems, commercial aircraft are equipped with transponders – a portmanteau of the words “transmitter” and “responder”. The main use of these telecommunications devices is to identify aircraft. But they are also deployed for emergency communications if the radio is down or a radio message isn’t appropriate in the given situation.

If the aircraft is being hijacked, for example, the code “7500” is entered. To help them remember this, trainee pilots learn the rhyme “75 – taken alive.” The code for radio failure is “7600”, while “7700” means there is an emergency. Assigned to the respective flight number, the code then appears on the screens of all air traffic controllers who are currently monitoring that flight’s airspace.

Airbus aircraft designations even indicate the engine variant

Also displayed on these screens is the respective aircraft’s registration number. But that’s not the only place it appears: the designation is invariably painted on both sides of the fuselage as well, where it is clearly visible. It functions in the same way as a car license plate – to give each and every commercial aircraft its own unique reference for identification purposes. In Germany, such designations are governed by the country’s Air Traffic Licensing Order (LuftVZO).

They begin with a “D-”—for example, D-ABYA. The next letter defines the maximum takeoff weight category. If this is over 20 metric tons, it will be an “A”. This is followed by the airline’s own designations; at Lufthansa, for example, a “B” stands for Boeing and a “Y” represents the 747-8 aircraft model. The final letter “A” indicates that this jet is the first 747-8 model delivered to the airline. Subsequent aircraft deliveries simply receive the next letter of the alphabet in the final position of their designation, i.e. D-ABYC, D-ABYD, D-ABYE.

Airframers can determine the name and classification of their aircraft types themselves. Airbus, for instance, calls an A320-200 an A320-230 if it is equipped with engines produced by the IAE consortium. The third number indicates the engine series, so the designation A320-231 denotes V2500-A1 engines.

Boeing aircraft don’t reveal such information, as the company opts to supplement its aircraft type designations with customer numbers only. For example, you can deduce that a Boeing 777-328ER belongs to the Air France fleet because “28” is the Boeing customer code for the French airline. Lufthansa has been allocated “30” as its Boeing reference. In Boeing code, therefore, D-ABYA would be a 747-830 aircraft operated by the German flag carrier.

Note that the runways in Geneva have not always been called 04/22 and 04L/22R, having been renamed from 05/23 and 05L/23R as recently as fall 2018. The reason is that unlike the Geographic North Pole, the Geomagnetic North Pole, to which compass needles are aligned, moves. Due to the varying distance between the two, the runways have to be renamed from time to time to ensure correct orientation. But that’s a whole other story.