aviation

Flying in the Concorde, the fastest of passenger jets

The British-French Concorde was the embodiment of the fast and luxurious jet set between 1976 and 2003. Andreas Spaeth flew in this legendary aircraft eight times. Here he takes a look back at the supersonic era.

author: Andreas Spaeth | 6 mins reading time published on: 19.06.2023

author:

Andreas Spaeth

has been traveling the world as a freelance aviation journalist for over 25 years, visiting and writing about airlines and airports. He is frequently invited to appear on radio and TV programs to discuss current events in the sector.

©Andreas Spaeth

“And yet, flying on the Concorde was always exciting and special. It was obvious that 1960s engineering had gone to extremes here to get passengers to their destination faster than a speeding bullet at the edge of space.”

Aviation journalist

As an aviation journalist, Andreas Spaeth flew on the Concorde a total of eight times between 1993 and 2003. Here he describes a journey aboard the supersonic jet from London Heathrow to New York. One of the last Air France Concordes landed for good at Paris-Le Bourget Airport in June 2003. Since then, it has been housed in the museum there and can also be visited as part of the Paris Air Show (June 19–25, 2023).

From start to finish, traveling on the Concorde was something special. First you checked in with British Airways in a separate area at London Heathrow, then you continued to the Concorde Room, an exclusive lounge. Tickets for the Concorde were notoriously expensive: average round-trip fare from London or Paris to New York, the only routes flown between 1976 and 2003, cost what was then 12,000 U.S. dollars. But that meant you would fly with a legend—and saved you considerable travel time, which was the main argument for supersonic flight. Instead of around eight hours, the flight across the North Atlantic took less than three and a half hours. The Concorde was literally a time machine: Flight BA001 departed London daily at 10:30 a.m. UK time; after traveling 5,833 kilometers across the ocean, it landed at JFK Airport in New York at 8:30 a.m. local time—earlier than it had departed. The Concorde was the only aircraft that, going by local time, could land before its departure time; hence the nickname “the time machine.”

©Andreas Spaeth

©Andreas Spaeth

©Andreas Spaeth

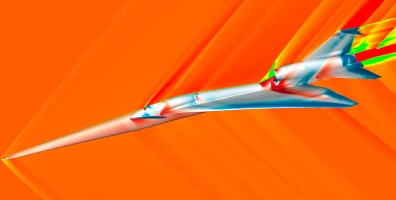

Twice the speed of sound: The Concorde celebrated its maiden flight on March 2, 1969, reaching Mach 2.02.

©Andreas Spaeth

©Andreas Spaeth

©Andreas Spaeth

High fuel consumption: The Concorde is equipped with the Olympus 593 engine.

In the air with Hugh Grant and Paul McCartney

One of the most exciting questions on all my Concorde flights was, “What celebrity is aboard today?” In the course of my supersonic flights, I met Liza Minnelli, Hugh Grant, Paul McCartney, and British royal Sarah Ferguson, among others, and had a bit of a chat with most of them. That sort of thing happened only on the Concorde; it was almost like a club. Many of the passengers were regulars. The crew knew exactly what they liked and always addressed them by name. First-time Concorde fliers were always most amazed by how small the plane was—a kind of flying pencil, a souped-up sports car of the skies.

The Concorde was cramped. Every time I boarded, I had to duck my head to get through the 1.67-meter-high door. The hundred-seat cabin offered about as much space for everyone as premium economy does today. Onboard entertainment was limited to a few audio programs, and the windows were only about the size of my palm. And yet, flying on the Concorde was always exciting and special. It was obvious that 1960s engineering had gone to extremes here to get passengers to their destination faster than a speeding bullet at the edge of space.

Also legendary: The Concorde’s fuel consumption and noise

From today’s perspective, the Concorde was extreme; an anachronism that scorned any attempt at sustainability. Take, for example, its incredibly high fuel consumption: it used the same amount of kerosene as a jumbo jet but carried only a quarter the number of passengers. In terms of fuel consumed per hour, a Boeing 787-9 today burns through only a quarter of what the much smaller Concorde used to. And the unbelievable noise at takeoff: getting the aircraft’s elegant delta wings, which were optimized for Mach 2, airborne in the first place required igniting afterburners—otherwise used only by military jets—on the four powerful Olympus engines.

That brief injection of kerosene into the hot exhaust gas stream increased thrust by 20 percent, but consumption by 50 percent. The Concorde took off at 400 km/h, its tremendous propulsion pressing the passengers back into their seats almost as forcefully as in a rocket launch—after all, the Concorde was really a kind of projectile. An amazing feeling. Shortly after takeoff, we crossed the Bristol Channel and overtook the first jumbo jet, which from above looked like it was hovering in place. After a quarter of an hour, we suddenly felt a little jolt, like a light kick, as the afterburners were activated again to help catapult us to supersonic speed. Only one minute later, the Concorde broke the sound barrier. Nobody on board could hear it, and passengers had only the speed indicator on the front cabin wall to assure them it was indeed the case. Mach 1.0, simple supersonic speed—and the Machmeter rose steadily to Mach 2.02.

©Andreas Spaeth

“Queen of the skies”: A British Airways Concorde on approach to Barbados.

Facts about the world’s fastest passenger jet

- Only 20 Concordes were ever built, twelve of which were in regular service with British Airways and Air France between 1976 and 2003.

- Final assembly of the aircraft took place in Toulouse and Filton; the Franco-British co production created the basis for the European Airbus consortium.

- Many technical achievements, such as the fly-by-wire controls that are now standard on every Airbus, were first implemented on the Concorde. The same is true for radial tires and carbon brakes.

- The cabin was designed to hold up to 148 passengers, but in scheduled service, there were never more than a hundred seats on board, with comfort levels equivalent to today’s premium economy class.

- The Concorde’s windows were the smallest ever on a commercial airliner—barely larger than the palm of an adult’s hand.

- During supersonic flight, the frictional heat would cause the temperature of the fuselage nose to rise to 127 degrees Celsius. Passengers could feel the heat inside on the window casings.

- In 2003, the standard round-trip fare for the Concorde’s London–New York flight was 6,636 British pounds (the equivalent of about 13,200 euros today).

- There is only one photo showing the Concorde during supersonic flight, because no other aircraft, not even a fighter jet, could match her speed.

- Thanks to the Concorde, British singer Phil Collins was able to perform twice at the Live Aid concert on July 13, 1985: once in Philadelphia and once in London.

- On February 7, 1996, Concorde made the flight from New York to London in a record time of 2 hours, 52 minutes and 59 seconds.

Space and the curvature of the earth just outside the window

The Concorde was now flying in the upper stratosphere at the edge of space. Peering out the window, I saw the vastness of the universe—the sky is almost pitch black even during the day. Looking down also offered a rare sight: as long as the horizon wasn’t blurred by clouds or haze, you could clearly see a slight arc in the line of the horizon—nothing other than the curvature of the earth. We were now flying at 57,000 feet (about 17,000 meters). “Only the astronauts on the International Space Station are higher than we are,” Mike Bannister, Chief Concorde Pilot for British Airways, once told me. “But they have to wear spacesuits, while we sit here in our shirtsleeves and travel 37 kilometers a minute.”

The aircraft seemed to be standing still; the tops of the nearest clouds were at least 6,000 meters below us, and there were no points of reference to be seen. In the time it took to read this short sentence alone, we had covered more than three kilometers. Although the air at this altitude is extremely thin and very cold (around minus 50 degrees Celsius), the heat generated by the friction of our flight was enough to warm up the aircraft’s aluminum alloy considerably. It got hottest at the tip: after two hours of supersonic flight, the Concorde’s nose could be as hot as 127 degrees Celsius.

An aircraft that stretches in flight

During each supersonic flight, the aircraft grew about 20 centimeters longer and shrank back to its original length at slower speeds until landing. To accommodate this, the aircraft had flexible wiring. There was only one place on board for this phenomenon to be observed, and that was the flight engineer’s instrument panel. Prior to takeoff, it fit snugly against the cockpit wall on the right, but after two hours in the air, there was suddenly a gap there so wide you could easily stick your hand in.

“Try it—but if you don’t take your hand out before we land, you’ll be trapped,” Bannister once joked to me when I got to ride in the particularly cramped cockpit. In my opinion, it was all too soon before he retracted the visor in front of the cockpit windows and then folded down the famous Concorde nose for landing. The airstream roared, and shortly afterward, our main landing gear was touching down on the runway at JFK Airport. This fascinating journey went by so quickly, that grasping the reality of having just arrived in America from Europe always took a little longer than the Concorde flight itself.

About the author

When he was just ten years old, aviation journalist Andreas Spaeth made a solo pilgrimage to the airport in his hometown of Hamburg to witness, up close and personal, the first and only Concorde landing there in April 1976. This fascination never left him, and as a young journalist, he flew it for the first time from Paris to New York in 1993 at the invitation of Air France. Seven more flights with operators Air France and British Airways followed, including on a jump seat in the cockpit (this was prior to the September 11 attacks). His last Concorde flight was from Paris to Karlsruhe in June 2003, on the Air France Concorde Fox Bravo, which has since been on display on the roof of the Technik Museum Sinsheim, alongside its Soviet counterpart, the Tupolev Tu-144. Spaeth has written several books on the subject of supersonic flight.