good-to-know

Green and economical – the promise of the new airships

Huge new cargo airships are poised to revolutionize logistics in remote areas. The builders of the latest generation have learned their lessons from history.

author: Andreas Spaeth | 6 mins reading time published on: 20.09.2023

author:

Andreas Spaeth

has been traveling the world as a freelance aviation journalist for over 25 years, visiting and writing about airlines and airports. He is frequently invited to appear on radio and TV programs to discuss current events in the sector.

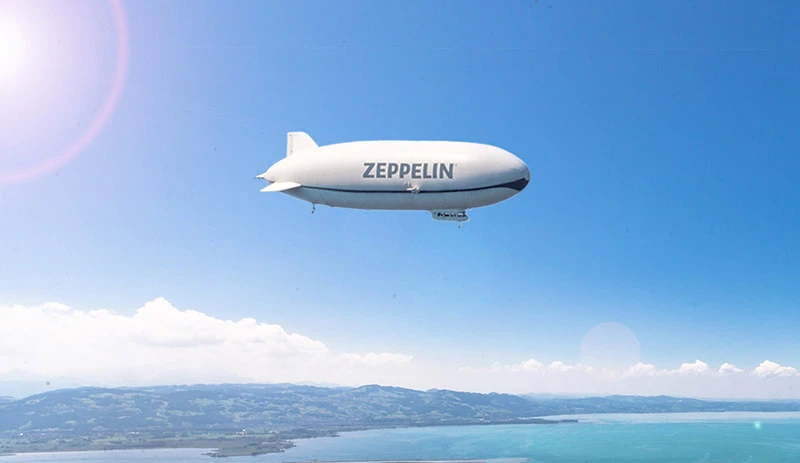

©Flying Whales

It’s barely 50 kilometers from Berlin Brandenburg Airport on Germany’s A13 highway before drivers see the world’s largest free-standing hall towering above the flat landscape on their left. What’s now a tropical water park was created in the 1990s for a vastly different purpose: constructing the CargoLifter, the largest airship in the world by far, measuring 260 meters from nose to tail—15 meters longer than the legendary Hindenburg zeppelin, the LZ 129 from the 1930s. But none of the CargoLifter giants ever came into being because by 2002, the company was already bankrupt. Nevertheless, Germany remains the home of these enormous “flying cigars.” For example, the only place in the world today where you can regularly book a passenger flight in an airship is the town of Friedrichshafen on Lake Constance in southern Germany. Here, modern Zeppelin NT airships take off for spectacular sightseeing flights between April and November. Those who have experienced it will never forget the sensation of floating gently, almost silently, over the landscape.

©Michael Häfner

Friedrichshafen on Lake Constance: Here, modern Zeppelin NT air-ships take off for spectacular sightseeing flights between April and November.

And the expertise of the company behind today’s Zeppelin NT is in demand worldwide; even the historic airship hangars in Sunnyvale, California, use components from Friedrichshafen. Sunnyvale is home to Moffett Federal Airfield, where America’s largest airships such as the U.S. Navy’s 240-meter Macon were stationed 90 years ago. And today, it’s the building site for an airship of the latest generation: the 122-meter-long Pathfinder 1. This was able to take off for the first time in May 2023, albeit only in the hangar and hovering just a few centimeters above the ground. Its passenger gondola and landing gear were made in Friedrichshafen. The company behind the project is LTA (“Lighter Than Air”), which is owned by Google co-founder Sergey Brin. LTA’s mission is to build a “green” airship: a high-tech structure made of carbon fiber that uses non-flammable helium as a lifting gas. Solar cells, batteries and electric motors are to be added in the future. Pathfinder 1’s missions are to be in the humanitarian field, quickly delivering aid to remote areas after disasters such as earthquakes. The new airships don’t need a landing pad; they can load or unload their cargo while hovering in the air.

40 percent of the lift comes from the shape

In recent years, as the development of sustainable flying machines has progressed, engineers and company founders in America and Europe have turned their focus back to airships for the first time. Now they have designed a new generation of “flying cigars”—not with conventional engines, but with electric or hybrid-electric propulsion, powered by fuel cells or solar cells on the outside of the shell. “It’s great to see that a number of companies are looking at the renaissance of the airship in the context of the need to reduce CO2 emissions in aviation,” says Prof. Uwe Apel, Professor of Aerospace Engineering at Hochschule Bremen—City University of Applied Sciences. For him, the most promising technological concept is the one for the American LTA Pathfinder.

©Hybrid Air Vehicles

Hybrid Air Vehicles: The Airlander is a so-called blimp, which does not have a rigid internal weight.

In Europe, the British company Hybrid Air Vehicles (HAV) is currently the furthest along. The unusual shape of its Airlander 10 when viewed from behind has earned the airship the nickname of “the flying bum.” That’s not a coincidence: this shape alone delivers 40 percent of the airship’s lift. The Airlander is a so-called blimp, which does not have a rigid internal weight. The airship hull is both the container for the lifting gas and the load-bearing system. In addition to freight transport, the vehicle will primarily be used for commercial passenger transport. The Spanish regional airline Air Nostrum has pre-ordered 20 Airlander 10s. As early as 2026, it hopes to operate the airships between Barcelona and Mallorca with an estimated flight time of four hours. There would be room on board for 100 passengers or 10 metric tons of cargo. Measuring 92 meters long and 42 meters wide, the vehicle will be able to reach a cruising speed of 130 km/h with a range of 3,700 kilometers. Work is also already underway on the much larger successor model, the Airlander 50, which will be able to carry up to 200 passengers or a payload of 50 metric tons.

©H2 Clipper

H2 Clipper: By 2029, this airship is expected to travel nearly 10,000 kilometers at a speed of 280 km/h

Purportedly able to fly much further and much faster is the H2 Clipper, which is currently being developed by the California company of the same name. By 2029, this airship is expected to travel nearly 10,000 kilometers at a speed of 280 km/h, powered by hydrogen fuel-cell electric motors. Its payload is expected to be up to 154 metric tons—about one-third more than conventional freighters. “The Clipper is designed for long-haul cargo transport,” explains company president Rinaldo Brutoco. “We see great potential in cargo flights between China and the U.S., for example.” The airship would need just under 36 hours to cross the Pacific. Depending on the future price of hydrogen fuel cells, “freight transport with the Clipper would be up to 75 percent cheaper than today—and also virtually emissions-free.” Furthermore, Brutoco predicts that, starting in 2029, “a large number of airships will be used for the carbon-neutral transport of green hydrogen.” He calls this planned global hydrogen delivery service Pipeline-in-the-SkyTM. Most importantly, the H2 Clipper would be the first airship since the Hindenburg disaster in 1939 to use hydrogen as a lifting gas. The European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) has allowed this since 2022, but approval in the U.S. is still pending.

©Flying Whales

Flying Whales: For instance, the large gondola of the Airlander 10 could comfortably house a crew of 16 for up to five days.

Gondola houses crew in comfort for five days

One player looking to the exceptionally large cargo segment as a market is French project Flying Whales, supported by government funding from its home country and from Québec, Canada. The 200-meter airship LCA60T would be able to unload huge wind turbine rotors directly at the most remote construction sites, fly mobile hospitals to disaster areas, or retrieve heavy tree trunks from impassable terrain. A total of 40 advance orders have already been placed. Professor Apel from Bremen certainly sees a potential market here, confirming that the French project has “the right approach,” although he feels it is not yet far advanced in its development. The new giants would also be suitable for use as high-altitude platforms, for, say, earth observation or mobile communications. For instance, the large gondola of the Airlander 10 could comfortably house a crew of 16 for up to five days. Airships offer the critical advantage of not being dependent on complex infrastructure such as ports or airports.

However, Prof. Jens Friedrichs, head of the working group on propulsors at TU Braunschweig, points out a serious problem with cargo airships: “During loading and unloading, lift and weight must be precisely balanced so that the airship doesn’t list and threaten to capsize. The processes suitable for this are either expensive or have so far not been sufficiently researched.” Moreover, the helium-filled flying hollow bodies are quite susceptible to failure during operation. “In storms, heavy rain or snowfall, it’s not enough to tie them to a mast,” says Friedrichs. “You need to put them in a massive hangar because their outer skin is very sensitive.”

“Nonprofit” flying is an advantage

Ask U.S. aviation analyst Richard Aboulafia if any of the new airship projects will change the market, and he’ll reply: “There’s always hope.” But he doesn’t see a business model: “It won’t scale for the passenger market. And as for the freight market, I can’t think of any goods that someone wants to ship faster and at a higher price than by ship, but slower than by air.” Of them all, LTA’s Pathfinder is seen in the most advantageous light: a roomy and stable airship with the key plus of flying humanitarian missions.