innovation

A step into the depths: MTU goes geothermal

MTU Aero Engines has once again broken new ground—this time, quite literally. From now on, the company will be using geothermal energy to provide heat at its Munich site. A project that combines the art of engineering with a pioneering spirit of sustainability.

author: Silke Hansen | 4 mins reading time published on: 16.12.2025

author:

Silke Hansen

is responsible for communication in the People & Culture department at MTU as a topic manager. Sustainability and quality are also part of her area of responsibility, because ultimately, people are what matters in all three areas.

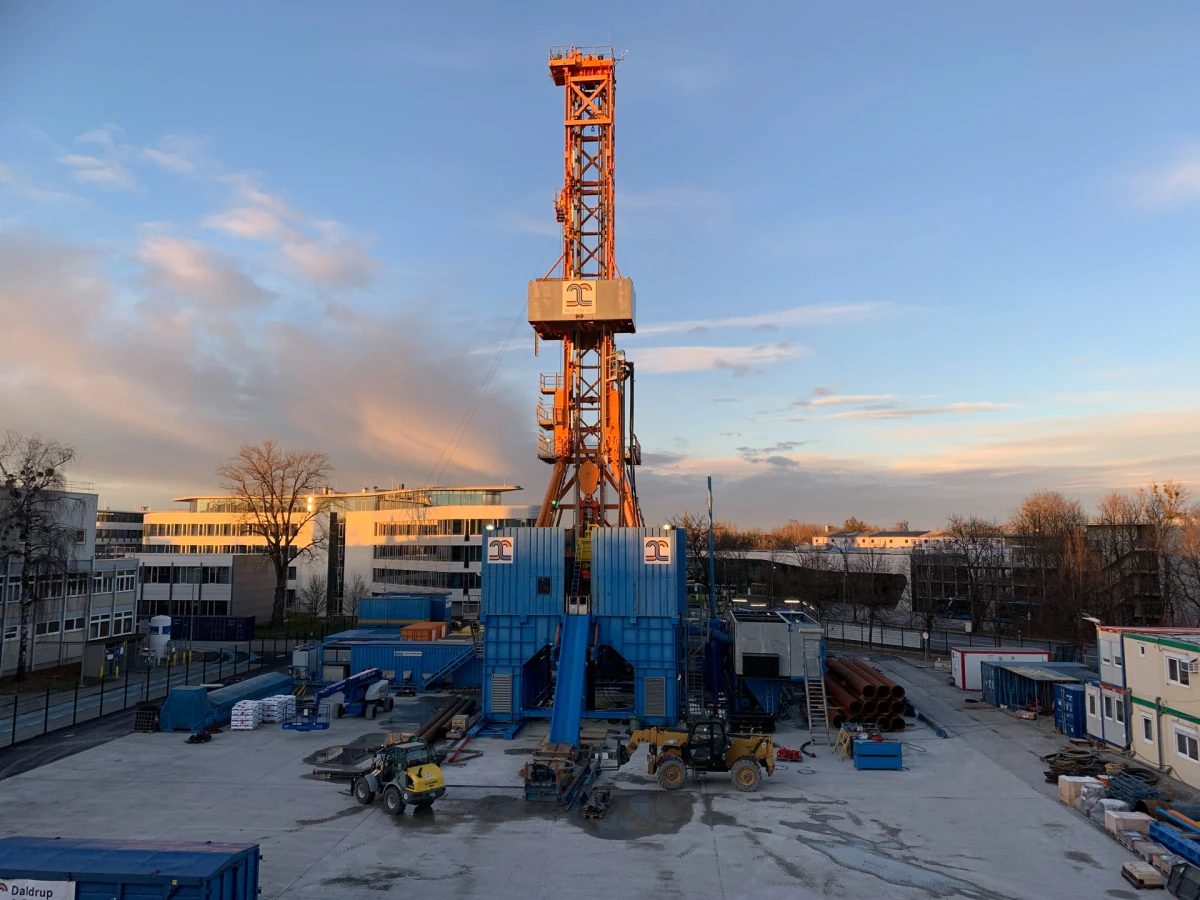

It’s the end of November 2025 in Munich and it’s raining cats and dogs on this late afternoon. As cold rain pours down from above, very hot water is gushing up from below; in the midst of it all, faces beam with pride and joy. MTU is celebrating a milestone—this time not in the air, but more than 2,100 meters underground. There, hiding in a layer of Jurassic limestone that formed around 150 million years ago, lies a reservoir of thermal water at a temperature of 71 degrees Celsius. And from now on, this source will provide the company’s Munich site with climate-neutral heat. With the official commissioning of its geothermal plant, MTU has completed a project that is without parallel in Germany. It has become the country’s first industrial company to harness its own deep geothermal energy.

“We aren’t just celebrating the launch of our deep geothermal energy today. We’re celebrating the courage to try something new and show that climate action and cost effectiveness aren’t mutually exclusive.”

Member of the Executive Board, Chief Operating Officer

“We aren’t just celebrating the launch of our deep geothermal energy today. We’re celebrating the courage to try something new and show that climate action and cost effectiveness aren’t mutually exclusive.”

Member of the Executive Board, Chief Operating Officer

During the project period from 2022 to 2025, two drilling operations were successfully completed – the first in 57 days, the second in 49 days.

Bavaria’s Minister of Economic Affairs and Energy Hubert Aiwanger and Silke Maurer, COO of MTU Aero Engines, at the official launch of the new facility at MTU’s Munich site.

Not flying high but delving deep

The idea of tapping into geothermal energy had been around at MTU for some time, but it was five years ago—before more recent energy crises and geopolitical conflicts brought security of supply into focus—that project manager Stefan Lange really got the ball rolling. “Geothermal energy is a core element of our company-wide ecoRoadmap climate strategy,” Maurer says. The strategy sets a goal for 2035 of reducing CO2 emissions across the MTU network by 63 percent compared to 2024, with each site free to go its own way to achieve this—from photovoltaics to heat pumps. The results are already impressive: Between 2019 and 2024, CO2 emissions fell by 42.2 percent.

But visions alone aren’t enough to turn an idea into reality. Here it took technical know-how and a good deal of miners’ courage. “We had to secure our own drilling rights and apply for a mining concession,” Lange recalls. MTU officially became a mining company. Now, instead of flying high, it would be delving deep. The decision to build the geothermal plant was made in 2022, and all the work was completed just three years later—including the deep drilling. This was all new territory for an aviation company.

Technology under high pressure

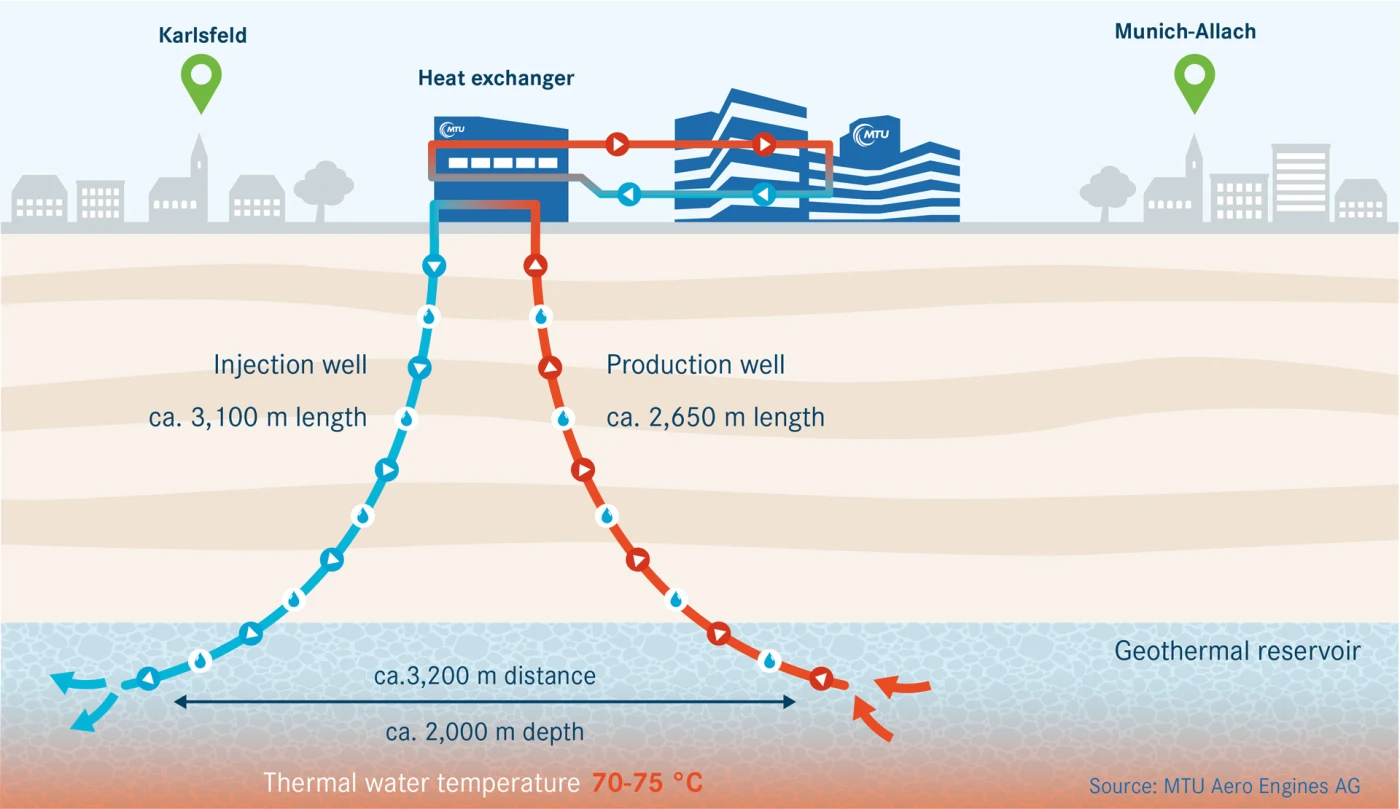

The new plant is based on a closed hydrothermal cycle. Two wells—a production well and an injection well—tap the thermal water at a depth of over two kilometers. A submersible centrifugal pump brings the hot water to the surface, where heat exchangers transfer its heat to the site’s heating network before it flows back into the ground. The plant’s pumping capacity is currently up to 90 liters per second; starting in 2027, a larger pump will be able to pump 150 liters. MTU’s geothermal plant currently has the most efficient production rate in Bavaria (measured in terms of the energy required to pump the volume of water).

How geothermal energy works: There are different types of geothermal energy and technologies for harnessing it. The process MTU uses in Munich (Allach) is hydrothermal geothermal energy. From a depth of around 2,200 meters, a production well pumps hot water at a temperature of around 70–75 degrees Celsius from a deep groundwater reservoir up to the surface. In a closed thermal water cycle, the heat can be transferred via heat exchangers to MTU’s heating network, causing the water temperature to drop to about 40 degrees. The cooled water is returned via an injection well to the same deep groundwater reservoir from which it was drawn. There, it heats up again, and the cycle begins anew.

Climate action and cost effectiveness

The technical facts are already impressive, but the ecological facts are even more so: From now on, geothermal energy will cover up to 80 percent of the site’s heating requirements with no CO2 emissions. This will save around 10,000 metric tons of CO2 and up to 56 gigawatt-hours of natural gas every year, or as much as is needed to heat 2,000 single-family homes. “Our investment will pay for itself in seven years,” Maurer states, “and the plant can operate for 50 to 100 years.” By making MTU largely independent of gas prices and supply, this adoption of geothermal energy is a poster child for cost-effective climate action.

At a glance: Geothermal energy at MTU

- Temperature of the thermal water: 71°C

- Depth of the wells: over 2,100 m

- Pumping capacity: up to 90 l/s (phase 1), 150 l/s (phase 2)

- CO2 savings: up to 10,000 t/year

- Output: 10–14 MW (corresponds to the annual heating needs of 2,000 single-family households)

- Project duration: 2022–2025

- Two wells: the first well was drilled in 57 days, the second in 49 days

Pioneering role for industry

“MTU has created a promise with geothermal energy: of heat from the depths and climate action for the future of our children.”

Project manager

“MTU has created a promise with geothermal energy: of heat from the depths and climate action for the future of our children.”

Project manager

The two wells are named Mathilda and Valentina after Stefan Lange’s daughters—and that’s no coincidence: These names symbolize the fact that this project combines technology and engineering skills with responsibility for future generations. “MTU has created a promise with geothermal energy: of heat from the depths and climate action for the future of our children,” Lange says. His delight is clear on this rainy November afternoon, as colleagues honor the completion of a project that’s both close to the civil engineer’s heart and has turned the Munich site into a pioneer for sustainable industry.