innovation

Blended wing body: The future of passenger aircraft?

Instead of a tube with wings, aircraft could soon have a blended wing body that functions as an aerofoil. This design promises up to 50 percent lower fuel consumption.

author: Andreas Spaeth | 6 mins reading time published on: 13.11.2024

author:

Andreas Spaeth

has been traveling the world as a freelance aviation journalist for over 25 years, visiting and writing about airlines and airports. He is frequently invited to appear on radio and TV programs to discuss current events in the sector.

©JetZero

Aircraft are masterpieces of engineering. They use the principles of aerodynamics to generate lift and minimize air resistance despite their weight. Modern aircraft do all this with their wings; the fuselage and other parts, such as the engines and tail assembly, increase drag and interfere with perfect aerodynamics. So wouldn’t it be ideal to design the whole aircraft to be buoyant? Over a hundred years ago, engineers were already fascinated by the idea of integrating everything into a giant flying wing: back in 1910, the German aircraft designer Hugo Junkers registered his flying wing patent, which was published in 1912.

And Junkers didn’t stop at theory: as early as 1929, he launched the largest commercial aircraft of the time—the huge Junkers G.38. In addition to housing its engines and fuel tanks on either side, the aircraft’s “thick wing”—which spanned a full 44 meters—could accommodate six passengers, giving each an excellent front-facing view. Today, only the military uses true flying-wing aircraft, such as the U.S. Northrop B-2 and B-21 stealth bombers. These aircraft do without a separate horizontal and vertical stabilizer and combine the fuselage and wings in a flowing shape that resembles a wing.

©Airbus Heritage

©Airbus Heritage

©Airbus Heritage

Junkers G38:The first aircraft was completed in October 1929. After initial taxiing tests on 4 November 1929, the first flight took place two days later with chief pilot Wilhelm Zimmermann at the controls.

Blended wing body for passenger flights

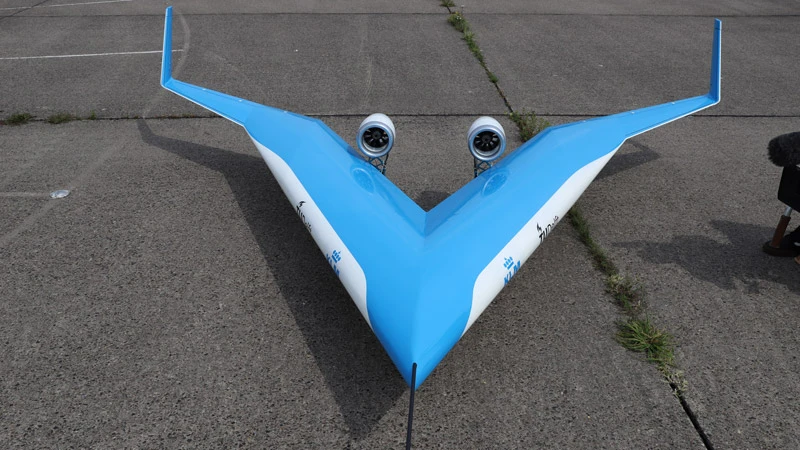

For commercial use, there’s an intermediate form between a flying wing and a conventional aircraft: known as the blended wing body (BWB), this concept brings together the conventional combination of tube and wing with the characteristics of a flying wing. The BWB is dominated by a flattened, aerodynamically shaped fuselage that merges smoothly into the wing. Such aircraft have so far been tested only as scaled-down experimental aircraft, such as the X-48 developed by NASA and Boeing, the Airbus MAVERIC, and the BWB-300 developed by the Chinese manufacturer Comac.

The U.S. start-up JetZero has been working on a new BWB generation, called Pathfinder, since 2021. With funding from the U.S. Air Force, NASA, and the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), this project is the closest to realizing a new form of passenger aircraft. Pathfinder will carry roughly 250 passengers and is aimed at the market currently served by Boeing 767 and 787-8 aircraft.

Pathfinder is set to carry passengers in 2030

In JetZero’s design, the aircraft will be no longer than current narrowbody jets, such as the Airbus A321 or the Boeing 757, but will have an impressive wingspan of 58 meters. The manufacturer is Scaled Composites, which is known for building the world’s largest aircraft, Stratolaunch, as well as Virgin Galactic’s carrier and space planes. A scaled-down demonstration model of Pathfinder is already under construction and is scheduled to take its maiden flight in 2027. Pathfinder’s commercial debut is planned for 2030.

Although the aircraft’s shape will be revolutionary, the technology behind it won’t be: “We’ll be relying heavily on existing components. The big innovation is the airplane itself,” explains Tom O’Leary, CEO and cofounder of JetZero. “But by using existing, certified components, such as turbofan engines for narrowbody aircraft, we can speed up the development process.” For its base model, JetZero has opted for the Pratt & Whitney PW2043.

©JetZero

Infrastructure compatibility: The JetZero blended wing aircraft integrates seamlessly into existing airport infrastructure. Its single-deck design fits existing runways and gates.

Easier to accommodate hydrogen tanks in a BWB

Alaska Airlines and the British low-cost airline easyJet are also banking on the BWB for the future. “The BWB has the potential to maximize efficiency while reducing fuel consumption and emissions by up to 50 percent,” explains David Morgan, Chief Operating Officer of easyJet. “The option to run Pathfinder on hydrogen in the future plays an important role.” The BWB’s curved shape can accommodate bulky hydrogen tanks in a more space-saving manner. “For airlines like easyJet, this means that a slightly bigger aircraft can both carry hydrogen and transport the same number of passengers as today,” O’Leary says.

It’s up to airline partners to clarify how airports could handle Pathfinder given its considerable wing dimensions. “An easyJet terminal can’t deal with a widebody aircraft,” O’Leary says, “but it can handle Pathfinder. You might have to adjust the line markings on the ground and reposition the passenger boarding bridges, but it will all be done using the same terminal.” He is certain of one thing: “The introduction of the BWB won’t fail just because people are reluctant to paint new lines on the apron.”

Proof of savings lacking so far

Claus Zeumer, an aircraft analyst in the Business Development and Strategy department at MTU Aero Engines in Munich, is following developments with interest: “BWBs promise structural and aerodynamic advantages. However, these concepts still have to prove that they can take all requirements into account and produce a better aircraft.” JetZero speaks of fuel savings of up to 50 percent, Zeumer reports, but he says: “It’s difficult to see how they came up with that number.”

The list of challenges for a BWB in scheduled service is long. The cabins will have to make do with fewer windows—a significant change for passengers. Passengers sitting nearer the plane’s extremities in particular will have to be prepared for noticeable vertical acceleration when the aircraft starts to turn. “Keeping to today’s turnaround times on the ground is also a challenge for BWBs and a key consideration for airlines,” Zeumer says.

Equipping the BWB with a pressurized cabin will likely be another sticking point. “The aircraft’s shape makes it particularly unsuitable for that. You need a tube with cabin pressure on the inside, while you have the aerodynamic contour shape on the outside,” explains Björn Nagel, Director of the Institute of System Architectures at the German Aerospace Center (DLR) in Hamburg. “The dimensions of a normal aircraft follow on almost entirely from the pressurized cabin. The fact that the BWB needs a pressurized inner hull plus an outside structure that has to be built around that hull makes it harder to achieve a weight saving compared to a competing aircraft.”

BWB as a tanker aircraft – a niche market

It’s quite possible that the BWB will start out not carrying passengers at all until the many hurdles it faces in everyday operations have been overcome. “The U.S. Air Force has repeatedly expressed an interest in having a tanker aircraft with a reduced radar signature. An appropriately designed BWB is better placed to achieve this than conventional configurations,” Zeumer says. “That would be a potentially lucrative niche market that JetZero could serve.” The Pathfinder concept is flexible enough to be used in the military sector, too, with conventional engines and 100 percent sustainable fuel.

“There’s a good chance we’ll see a BWB tanker aircraft take to the skies in the future. Then only the cockpit would need to be pressurized, which would be much easier than pressurizing the entire passenger cabin. To achieve the desired stealth effect, the engines could be integrated into the airframe to a greater extent than is currently the case with JetZero,” Zeumer says, adding: “In commercial aviation, it’s going to be a bumpy ride.” Today’s aircraft are the result of over a century of technical evolution and have very balanced characteristics. But that’s not to say things will stay that way forever: “Changing requirements and new technologies can encourage new configurations.”