aviation

Fifty years ago, the Airbus A300 made history

Taking off together: A large aircraft for short distances, the original Airbus A300 was Europe’s attempt to compete with U.S. jets half a century ago.

author: Andreas Spaeth | 6 mins reading time published on: 07.11.2022

author:

Andreas Spaeth

has been traveling the world as a freelance aviation journalist for over 25 years, visiting and writing about airlines and airports. He is frequently invited to appear on radio and TV programs to discuss current events in the sector.

©Airbus SAS

The long-anticipated maiden flight of the first Airbus A300 prototype, the A300B, had to be postponed twice due to weather. But on October 28, 1972, the big day finally arrived: Europe’s first widebody aircraft took its maiden flight—yet eyewitnesses were few. In Toulouse and everywhere else in France, the Concorde was the number one priority at that time.

This was already obvious at the presentation ceremony one month prior, where the second Concorde prototype, which had been manufactured in Toulouse as well and had its maiden flight three years before, was brought out in front of the hangar first, followed by the Airbus shortly thereafter. Participants report that the more than 1,000 guests of honor all ran directly to the Concorde, which, in contrast to the somewhat stocky workhorse that was the A300B, exerted a magical attraction.

©Airbus SAS 1972

©Airbus SAS 1972

©Airbus SAS 1972

September 27, 1972: Presentation ceremony of the first Airbus A300 prototype.

©Airbus SAS

©Airbus SAS

©Airbus SAS

October 28, 1972: The maiden flight crew included captain Max Fischl, Bernard Ziegler as copilot, and flight engineer Günther Scherer.

A complex production chain

At that time, Europe wanted to finally challenge the dominance of U.S. suppliers such as Boeing and Douglas with a joint aircraft project. In addition to the Concorde project, which was already in full swing, plans were made for a conventional, twin-engine passenger aircraft with 300 seats (hence the designation A300). In 1969, after lengthy negotiations, Germany and France agreed to collaborate on the project as key partners. Logistically, this was a highly complex endeavor, with aircraft production sites spread across dozens of locations throughout half of Europe. Various parts had to be transported to Toulouse for final assembly from facilities in northern Germany and England as well as Saint Nazaire and Nantes in France.

October 1970 marked the official start of the program. Work on the first A300 prototypes commenced soon after. Meanwhile, their passenger capacity had been reduced to some 250 seats at Lufthansa’s request. Also new was that an aircraft this size was to fly more quietly and more economically with just two engines instead of three or four, as was usual at the time.

©AIRBUS

A flying success: The A300 sold 561 units, 229 of which are still flying, mainly as freighters.

Flight test program over the Pyrenees

At 10:39 a.m., the Airbus prototype started taxiing along the runway and took off 30 seconds later, propelled by two of GE Aviation’s CF6-50 commercial engines. On the aircraft that morning were captain Max Fischl, Bernard Ziegler (son of Airbus CEO Henri Ziegler) as copilot, and flight engineer Günther Scherer. For almost two hours, the crew ran its test program high above the Pyrenees—all went well. Then they returned to Toulouse, where the pilots landed the aircraft in strong crosswinds.

But the challenges were only just beginning. The A300B still had to go through the flight test program, required certification and had to be established on the market. At the time of its maiden flight, only ten orders had been received: six from Air France and four from Iberia.

The foundation for becoming the world market leader

Flight testing was still in progress when Airbus took the A300B on extensive demonstration tours to America, Asia and Africa. At the time, most people at Airbus were already convinced that the future belonged to Airbus, not Concorde. The A300B received its certification on March 15, 1974, after 1,585 flight hours—six weeks ahead of schedule. A couple months later, on May 23, Air France launched its first scheduled flight with an Airbus.

The program had to survive some dry spells. It wasn’t until 1977 that it broke into the crucial U.S. market with an order from Eastern Airlines. The A300B achieved success a few years later, followed by the shorter A310 in 1983. This laid the foundation for becoming the world market leader in commercial aircraft, a distinction based on number of orders. Airbus first achieved this title in 1999 and has been able to defend it in eight out of ten years since 2011. The A300, which was discontinued in 2007, eventually sold 561 units, 229 of which are still in service, mainly as freighters.

©AIRBUS

©AIRBUS

©AIRBUS

Zero gravity: Parabolic flights let astronauts achieve weightlessness without going into space.

©Airbus SAS 2022 Ben cooper

©Airbus SAS 2022 Ben cooper

©Airbus SAS 2022 Ben cooper

BelugaST: Unloading of the Hotbird 13G satellite at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

A300Bs aged 40 and over are still flying passengers

According to Airbus, 26 first-generation A300B aircraft are still flying passengers today, in some cases after over 40 years of service. Many of them are in Iran due to an international embargo on supplying the country with newer aircraft types. In 1996, the A300 was repurposed for a special mission: parabolic flights that allow researchers and astronauts to experience zero gravity. It has since been replaced in this capacity by an A310.

Right now, the average age of active A300/A310 aircraft is 28 years. “In 2021, these were the third most-used freighters worldwide, beaten only by the Boeing 757 and 767,” says Pascal Vialleton, Head of the A300/A310 program at Airbus. “The A300 is the backbone of the fleets of freight forwarders FedEx, UPS and DHL—and there are no plans to decommission these aircraft.” Two stages of technical modification can expand the service life of A300-600 freighters to as many as 51,000 cycles (one takeoff and one landing per cycle) or 89,000 flight hours. Even the most-flown units have yet to reach this limit.

The A300-600 plays another important role for Airbus—as the base model for the BelugaST (also known as A300-600ST Super Transporter), a giant transporter designed to carry large aircraft parts between the European sites. Since 1995, Airbus has been employing five BelugaST aircraft, which only recently obtained an ETOPS 180 rating for transatlantic flights (ETOPS 180 means an aircraft can fly routes up to three hours from the nearest airport). Airbus considers this an important ability for the BelugaST to have as it is now entering commercial use, for instance in satellite transportation. The aircraft’s previous function of transporting aircraft parts will be taken over by the even larger Beluga XL. It’s clear that even after half a century, the story of the A300 is far from over.

The CF6: A milestone for MTU

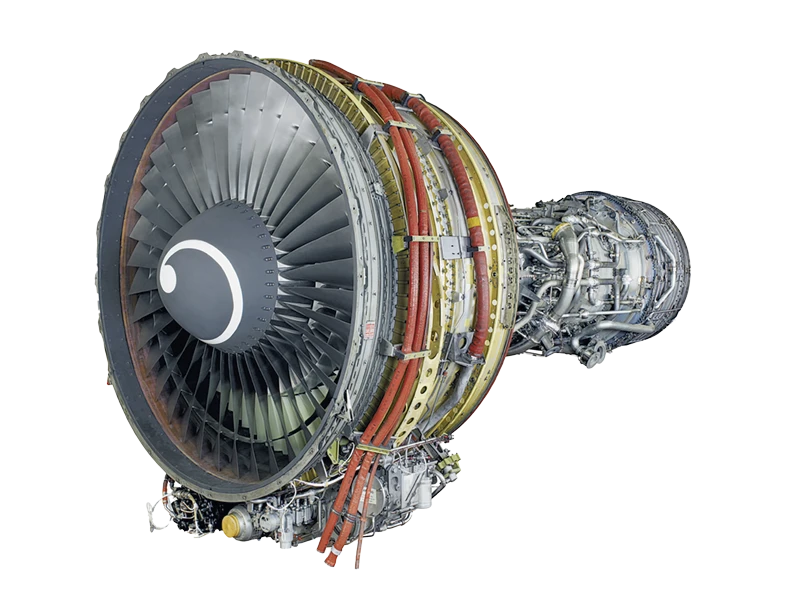

CF6-50: The model is among the bestselling engines of its class and was MTU’s first engine for commercial aviation 50 years ago.

February 9, 1971, was an important day in MTU’s history. That’s when the Munich-based engine manufacturer signed a partnership contract with U.S. company General Electric (GE) for the new CF6 engine. MTU’s program share is about 9 percent. The German company manufactures several turbine and compressor components exclusively for GE. This turbofan, with its high bypass ratio, was originally intended for a new generation of widebody aircraft such as the DC-10 or the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar. In 1971, the CF6-50 won the contract from Air France for the first six aircraft. The A300 prototype that first took off 50 years ago was also fitted with CF6-50 engines.

“It was an important milestone: the first time MTU joined a commercial engine program and was able to bring its military experience to bear as a partner,” says Johann Sattler, Head of CF6 Program Management at MTU. Half a century later, the CF6 is far from being a thing of the past. “There are still almost 1,500 aircraft with CF6 engines in active service,” says Claudia Gaab, Director GE Programs at MTU. At present, some 60 units of the latest version of this engine type are being manufactured every year. Many of them go into Boeing 767 commercial freighters, which will be produced at least until 2027. Over the course of half a century, MTU has manufactured over a million individual parts for the CF6 at its Munich site.

All CF6 versions put together have logged more flight hours than any other widebody aircraft engine to date. “It’s impressive that the CF6 became such a success and is still generating a significant portion of MTU’s revenue and earnings 50 years later—nobody could have foreseen that level of success back then,” Gaab says. “And because the engine series has such a long service life, the spare parts business, too, is much greater than originally anticipated.” The contract with GE that was signed in 1971 has, to this day, served as a model for further mutual agreements. “The 1971 agreement laid the foundation for MTU’s continued partnership with GE in many other programs, such as the GE9X and the GEnx, which gradually expanded their collaboration. This would not have been possible without the CF6 engine,” Gaab says.