aviation

Germany as pioneer: The dream of vertical takeoff

Vertical takeoff aircraft ought to have revolutionized German aviation 50 years ago with the Dornier Do 31 as a V/STOL transport aircraft with military and commercial applications.

author: Andreas Spaeth | 7 mins reading time published on: 08.03.2023

author:

Andreas Spaeth

has been traveling the world as a freelance aviation journalist for over 25 years, visiting and writing about airlines and airports. He is frequently invited to appear on radio and TV programs to discuss current events in the sector.

©Airbus Corporate Hertiage

Vertical takeoff air taxis are high up on the aviation agenda for the 2020s. Soon you could be catching one from outside your front door, or at least from downtown locations previously unsuitable for air traffic. But let’s first go back over half a century, when Germany was poised to usher in the golden age of vertical takeoff aircraft for commercial passenger flight. Striking colorful illustrations document how the planners of the time envisioned vertical takeoff aircraft that would depart from locations like the roof of Munich’s central train station.

©Airbus Corporate Hertiage

©Airbus Corporate Hertiage

How Munich’s central station might look today—or so some thought 50 years ago. A multimodal transport hub with STOL-port on the roof.

©Airbus Corporate Hertiage

Engineers have always been fascinated by the notion of building machines that combine the advantages of helicopters with those of fixed-wing aircraft. The appeal lies in aircraft that require neither a runway nor momentum to get airborne, but rather take off under their own power before switching to efficient cruising flight. In 1922, a French-made quadcopter became the world’s first aircraft to take off vertically and fly reliably. But it would be another 40 years before the first vertical takeoff jets appeared.

Vertical takeoff from the highway

Development was driven by the Cold War and by the fear that tensions could erupt into a full-blown conflict. Germany would then have been on the front lines, with many airfields located close to the inner German border, which at that time separated NATO allies from the members of the Warsaw Pact. To be able to quickly relocate fighter jets to more remote areas and launch them if needs be from highways, the West German Air Force turned to vertical takeoff aircraft.

As early as 1959, the West German government green-lit three experimental industrial programs: a supersonic interceptor, a subsonic reconnaissance fighter and a transporter jet. These efforts produced the VJ101 C (a vertical takeoff fighter jet, maiden flight 1963) and the VAK 191B (a vertical takeoff reconnaissance and strike aircraft, maiden flight 1971). But the crowning glory of these programs was the only transport aircraft with vertical/short takeoff and landing (V/STOL) capabilities ever built: the Dornier Do 31. It was designed to fly at around 700 km/h and carry a payload of up to six metric tons, which is roughly equal to a three-ton truck complete with troops, or up to 36 fully equipped soldiers.

©Airbus Corporate Heritage

©Airbus Corporate Heritage

©Airbus Corporate Heritage

The Do 31 prototype first achieved hover flight at the Dornier site in Oberpfaffenhofen in 1967.

©Airbus Corporate Heritage

©Airbus Corporate Heritage

©Airbus Corporate Heritage

On its maiden flight in 1967 , the Do 31 had a takeoff weight of 19.3 metric tons.

©Airbus Corporate Heritage

©Airbus Corporate Heritage

©Airbus Corporate Heritage

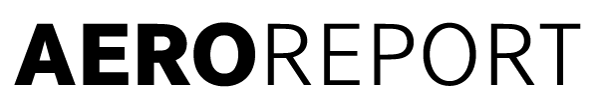

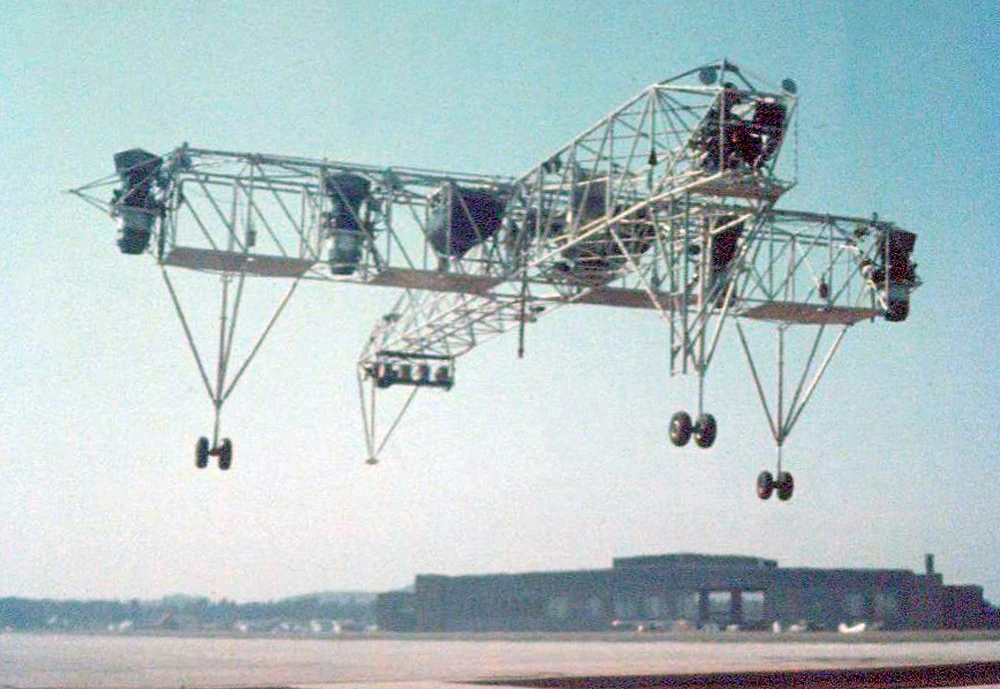

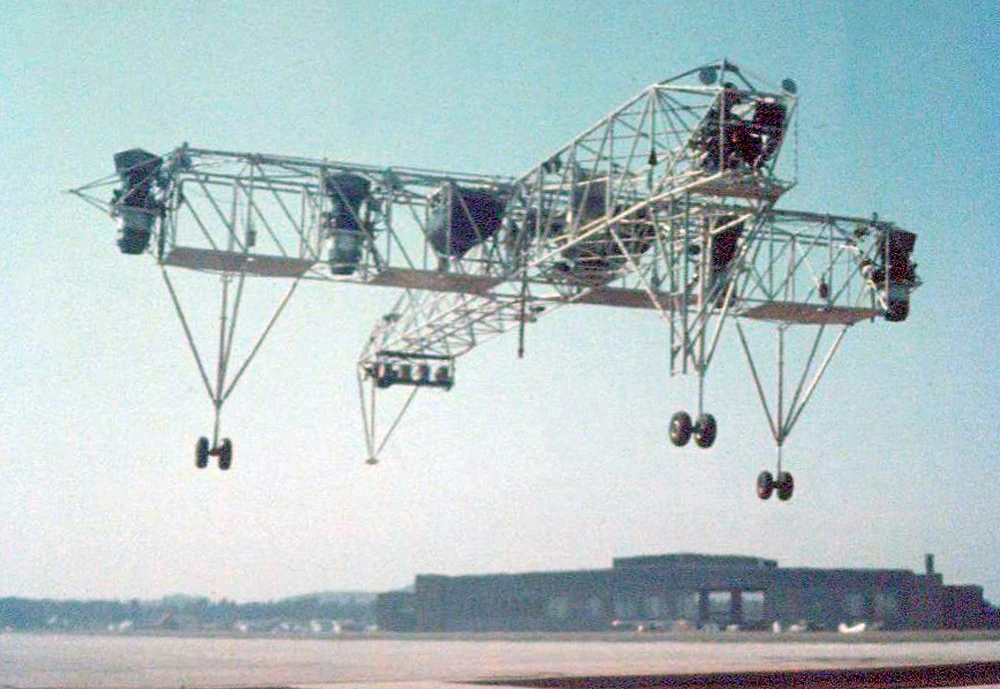

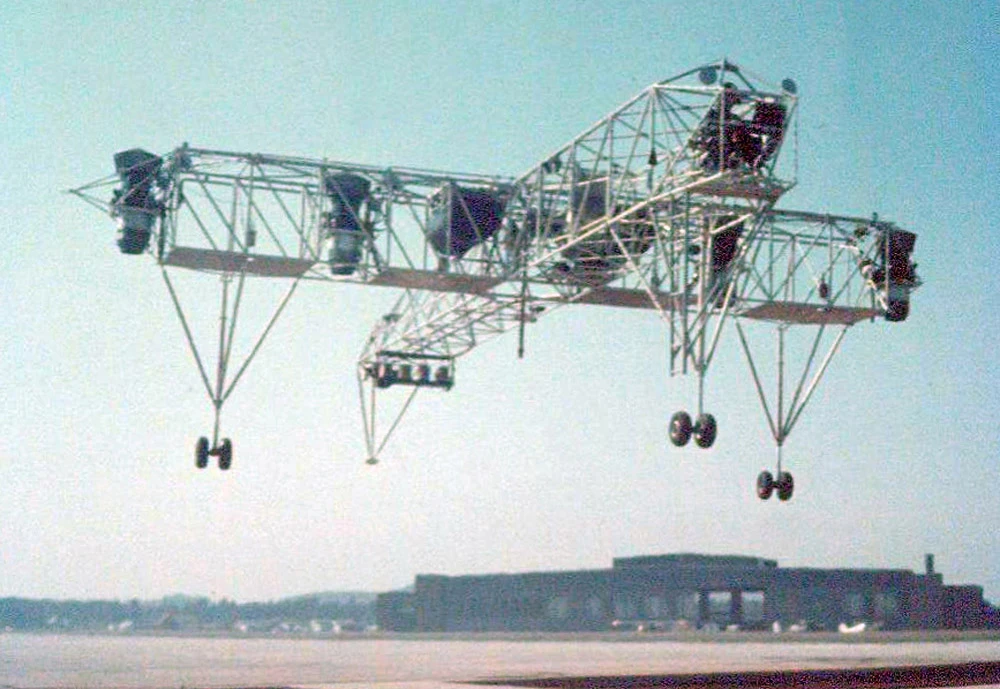

Its predecessor—the control test airframe—first took off back in 1964; test priorities included hover regulation and controls.

©Airbus Corporate Heritage

©Airbus Corporate Heritage

©Airbus Corporate Heritage

The entire test fleet assembled in Oberpfaffenhofen: the large hover rig (with red nose), first tested in 1965, and the two Do 31 prototypes E1 and E3.

Military vertical takeoff aircraft remain a niche product

For many air forces, the hype surrounding vertical takeoff aircraft didn’t last long, ending before this kind of aircraft could become properly established. The technical problems proved immense. Only the British Hawker Siddeley Harrier overcame them, entering service as a VTOL ground-attack aircraft in 1969. Including its successor, the Harrier II, which was produced until 2003, a total of 670 of these aircraft were delivered and deployed, for instance on aircraft carriers. In 1971, the Soviet Union began deploying its counterpart, the Jak-38, which was retired in the mid-1990s. No successor was planned.

More than 40 VTOL models made it into the air

The biggest challenge remained the crucial transition from hovering to level flight—a maneuver that cost many test pilots their lives. In 1981, Bell and Boeing began developing the V-22 Osprey. After a series of devastating setbacks, the Osprey became the first production military tiltrotor helicopter; it has been in service with the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Marine Corps since 2005. There have been many VTOL military jet projects over the years, and although more than 40 different models have made it into the air, none other than those mentioned above entered large-scale production. At the moment, the focus is on the Lockheed Martin F-35B, the fifth generation of the multirole stealth fighter, which is designed primarily for deployment on aircraft carriers. With its short takeoff and vertical landing (STOVL) capabilities and vectoring thrust nozzles, this aircraft is already being used by the U.S. Marine Corps, and by the British Royal Air Force as replacement for the Harrier.

The Lockheed Martin F-35B is the only modern vertical takeoff aircraft that was specially designed to be deployed on aircraft carriers.

Lift and cruise engines: complex mechanical construction

The engineers decided against pivoting engines. Instead, they installed wingtip nacelles, each with four Rolls-Royce RB162 turbojets as lift engines—weighing just 127 kilograms a piece but producing two metric tons of thrust. Under each wing, there was a cruise engine equipped with pivoting thrust nozzles, which also aided vertical takeoff. These two engines were Bristol Siddeley (today Rolls-Royce) Pegasus 5-2 turbofans, which were also used in the Hawker Siddeley Harrier—still the most successful V/STOL aircraft ever produced. Not even the most powerful helicopter available at the time had the lift capability of a Do 31 with its maximum takeoff weight of 24.5 metric tons.

On February 10, 1967, the Do 31 took off on its maiden flight from Oberpfaffenhofen near Munich with an initial takeoff weight of 19.3 metric tons. This milestone is made all the more impressive considering that the highly complex challenges concerning the aerodynamics, engine arrangement, flight control and the control-pilot interface were solved using 1960s technology. The control system, which had to manage a precision interaction of lift and cruise engines close to the ground, was a complex mechanical construction. It featured an early version of fly-by-wire, the electronic flight control system, which at the time was being adopted for the Concorde and would later become the backbone of the Airbus cockpit.

Setting still unbroken world records on the way to Paris

The Do 31 came of age in what in any case was a most eventful year in the history of global aerospace. In 1969, both the Concorde and the Boeing 747 had their maiden flights, while the moon landing captivated the world. It seemed anything was possible. Shortly before the moon landing, the Do 31 had set multiple world records for jet-powered vertical takeoff aircraft in its weight class on its ferry flight from Oberpfaffenhofen to the Paris Air Show. One of these was completing the journey in just one hour 19 minutes—a record that has yet to be beaten. Like all vertical takeoff aircraft, however, the Do 31 did have some major drawbacks: it consumed vast amounts of kerosene, which was as objectionable as the noise level both inside and out.

“People in and around Oberpfaffenhofen got scared when the ground shook and they heard the plane’s unbelievable roar, which was nothing like normal aircraft noise,” said German test pilot Dieter Thomas, who died in 2013, in an interview. His colleague Drury Wood, who died in 2019, noted: “This ten-engine aircraft got so incredibly loud that it caused damage.” He was referring to damage to both health and property.

Nevertheless, at the time there were big plans to use vertical takeoff aircraft to transport passengers. Indeed, Dornier had already presented a modified design of the Do 31, dubbed the Do 231. Designed as a shoulder-wing aircraft, the Do 231 was earmarked for Lufthansa as a 100-seater with a maximum speed of 900 km/h and a range of just under 3,000 kilometers. Equipped with a total of 12 lift engines, it could have managed a takeoff weight of 59 metric tons and was set to enter service in 1977/1978.

©Airbus Corporate Hertiage

Artist’s impression of the commercial version of a vertical takeoff aircraft for 80 to 100 passengers that was planned in 1969. Lufthansa was interested in the proposed Do 231.

The oil crisis dashed all dreams of commercial vertical takeoff aircraft

Unfortunately, the international situation at the time was anything but conducive for vertical takeoff aircraft. The West German government started cutting research budgets as early as 1967, including for the Do 31. Vertical takeoff aircraft also lost strategic importance for the military, and the 1973 oil crisis dashed all dreams of commercial applications. Decades later, Airbus Group historians stated that, “From today’s perspective, it’s really hard to understand the hype that surrounded vertical takeoff aircraft in the ’60s. The technology of the time would be in no position to comply with today’s efficiency and noise standards.

Today’s engines perform considerably better while also being much quieter and more efficient.” They recognized, however, that considerations are different for special missions, as demonstrated for instance by modern tiltrotor aircraft like the Bell-Boeing V22 Osprey. Germany’s engineers of over 50 years ago were definitely ahead of their time, and their early concepts could well inspire present-day practitioners. The buildings in Oberpfaffenhofen in which the Do 31 was designed have since been modernized. As it happens, they are now home to the company Lilium, which is working on an electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft.

A tiltrotor aircraft with commercial applications

Emitting only a low buzz, the AW609 takes off lightly, hovers and actually flies briefly backward. Slowly, the twin-rotor nacelles turn, shifting the orientation of the large rotors from horizontal to vertical for forward thrust. Now the aircraft really picks up speed. Most conventional helicopters tend to cruise below 3,000 meters and rarely achieve a cruising speed of more than around 260 km/h. In contrast, with its nine-seater pressurized cabin, the AW609 flies at an altitude of over 7,600 meters and can travel 1,800 kilometers at a speed of 500 km/h. It can take off from and land on parking lots, the roofs of buildings and offshore drilling rigs. This is the whole idea of what are known as tiltrotor aircraft.

The offshore industry is a key target group

After more than two decades in development, the AW609 had its maiden flight in 2003. Its name dates back to its previous manufacturer, AgustaWestland. But now it’s the Italian-American manufacturer Leonardo that might actually manage, possibly by 2024, to bring the second approved tiltrotor helicopter powered by Pratt & Whitney PT6C-67A engines to market—the first ever such aircraft for commercial applications. The offshore industry, which up to now has used helicopters to reach drilling platforms out at sea, is one of the most important target groups for the commercial use of tiltrotor variants.

©Leonardo

By 2024, the Leonardo AW609 could become the only tiltrotor aircraft to be certified for commercial use, for example in offshore transport.

Previous tiltrotor projects were often very expensive and prone to setbacks, and the current approval process is no different. After all, an aircraft with drive propellers that change the direction of thrust by tilting on the lateral axis has never before been used in a commercial setting. This is also new territory for the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Approval for the AW609 will be based on a combination of existing standards for its air transport category and new tiltrotor regulations. “This is the FAA’s first new aircraft category in several decades,” says Matteo Ragazzi, Chief Engineer at Leonardo, “so they will have to also look beyond the AW609 and create a framework for all current and future aircraft in this class.”