good-to-know

How does a turbojet engine work?

Propulsion for the most demanding conditions: turbojet engines are highly specialized for military applications. But how do they actually work?

author: Patrick Hoeveler | 5 mins reading time published on: 17.06.2024

author:

Patrick Hoeveler

is a freelance aviation journalist working for FLUG REVUE and other publications.

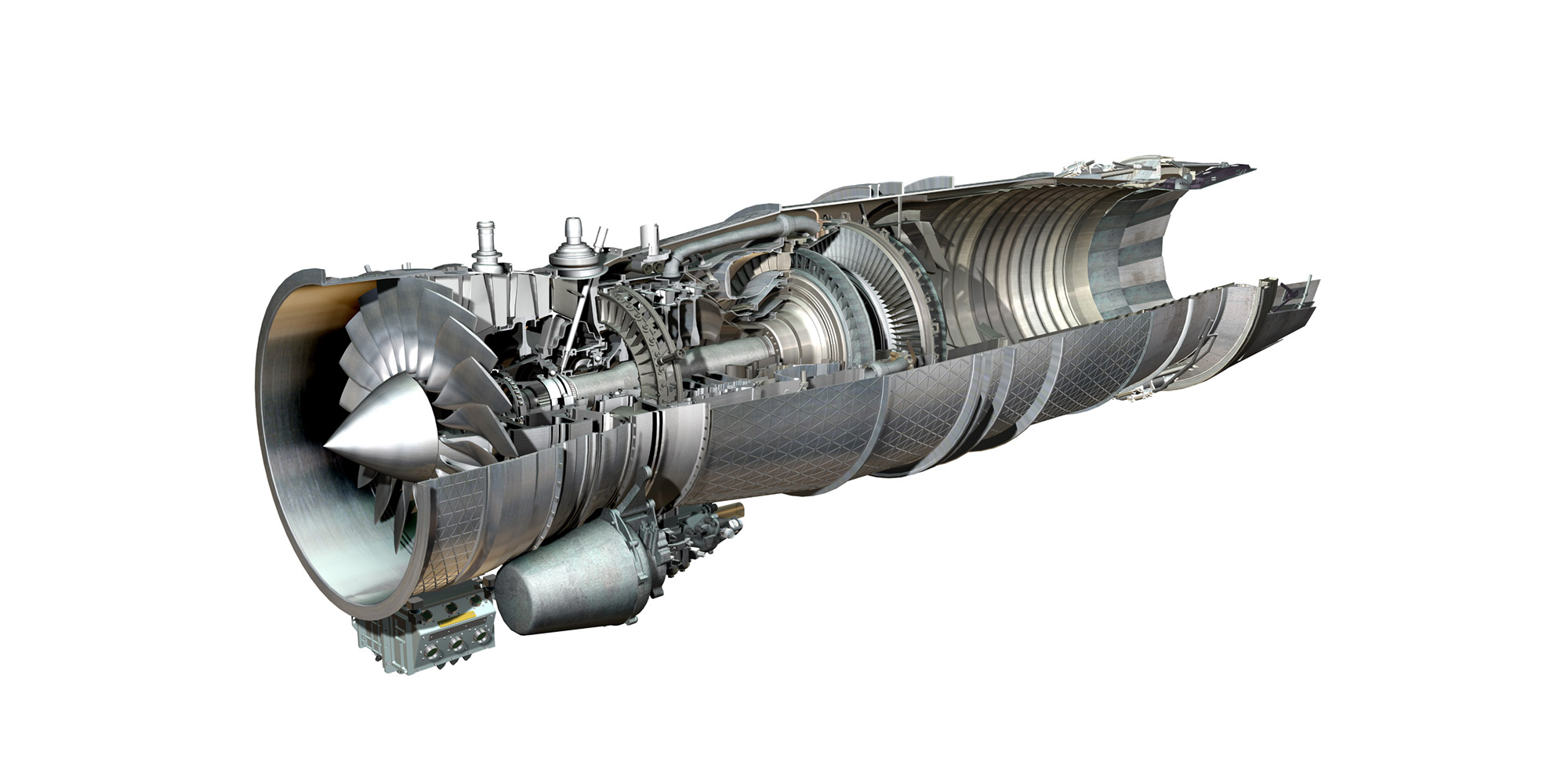

Next to a commercial turbofan engine with its giant fan, a sleek military turbojet looks almost a little lost. But in fact they function in basically the same way: air is compressed, mixed with fuel, and ignited. This generates an enormous amount of energy, which both drives the turbines and provides forward thrust. However, the requirements for the respective engines couldn’t be more different.

Commercial engines are naturally optimized for cruising flight, as this is the flight envelope in which the aircraft spend most of their time. The focus is on keeping fuel consumption and noise to the lowest possible level. Military propulsion systems have to accelerate a relatively small mass to very high speeds and also deliver thrust in the supersonic range. In contrast to commercial turbofans, which use a large fan to achieve high propulsion efficiency, turbojets have a much smaller fan to ensure a high exit velocity. This means that less air flows through the engine, but the acceleration is higher.

Turbojets are highly specialized engines designed for maximum performance under the most demanding conditions. Although they basically function in a similar way to commercial engines, their focus is clearly on the specific requirements of military applications.

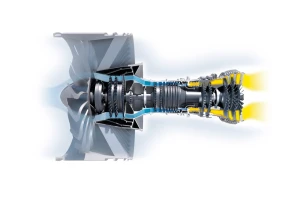

How a turbojet engine works

Ingestion:

The air is sucked in through the engine’s front opening, called the inlet. At high speeds, especially in supersonic flight, the design of the inlet plays a critical role as it must efficiently direct the airflow to the compressor while minimizing shock waves and drag.

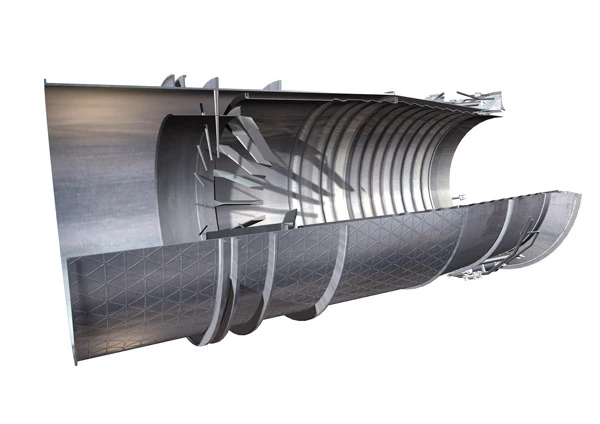

Compression:

After the air has been ingested, it first flows through the low-pressure compressor and then through the high-pressure compressor. Each stage compresses the air further, increasing its pressure and temperature. This compression is essential to maximize the efficiency of the subsequent combustion and thus generate greater thrust.

Combustion:

After compression, the air flows into the combustor. This is where fuel-injection nozzles create a mix of fuel and air, which is then combusted at a temperature of over 2,000 degrees Celsius. The buildup of heat causes the gas to expand to several times its original volume and escape at high energy from the combustor, where it is responsible for driving the turbines, which also power the compressors.

Expulsion (with afterburner):

After the gases have flowed through the turbine, they enter the afterburner, where additional fuel is injected directly into the hot exhaust gas flow and ignited. This further combustion significantly increases the temperature and thus the exit velocity. As the gases are now expelled at an even higher speed, this generates much greater thrust.

How a turbojet engine works

Ingestion:

The air is sucked in through the engine’s front opening, called the inlet. At high speeds, especially in supersonic flight, the design of the inlet plays a critical role as it must efficiently direct the airflow to the compressor while minimizing shock waves and drag.

Compression:

After the air has been ingested, it first flows through the low-pressure compressor and then through the high-pressure compressor. Each stage compresses the air further, increasing its pressure and temperature. This compression is essential to maximize the efficiency of the subsequent combustion and thus generate greater thrust.

Combustion:

After compression, the air flows into the combustor. This is where fuel-injection nozzles create a mix of fuel and air, which is then combusted at a temperature of over 2,000 degrees Celsius. The buildup of heat causes the gas to expand to several times its original volume and escape at high energy from the combustor, where it is responsible for driving the turbines, which also power the compressors.

Expulsion (with afterburner):

After the gases have flowed through the turbine, they enter the afterburner, where additional fuel is injected directly into the hot exhaust gas flow and ignited. This further combustion significantly increases the temperature and thus the exit velocity. As the gases are now expelled at an even higher speed, this generates much greater thrust.

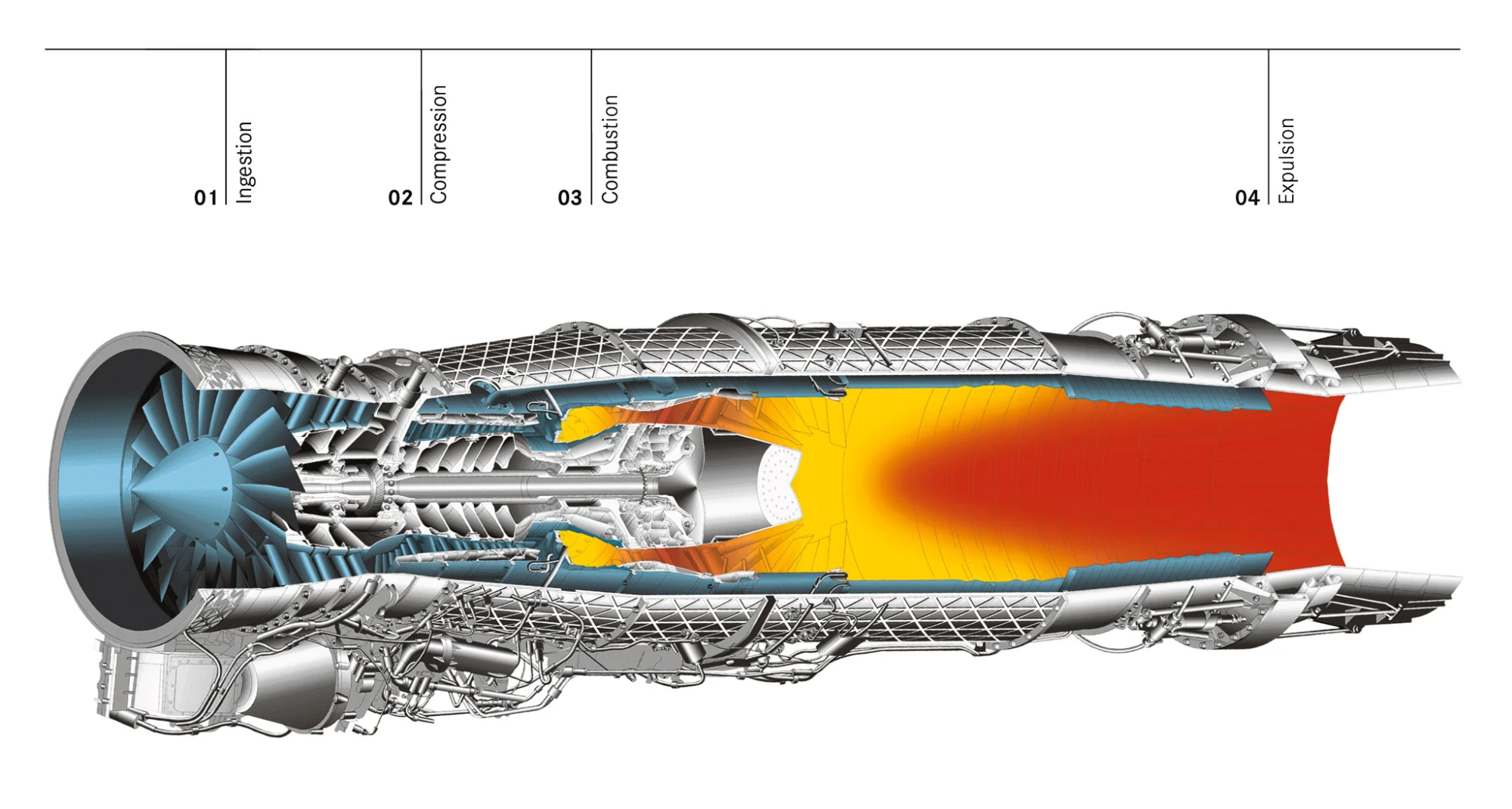

Design of a turbojet engine:

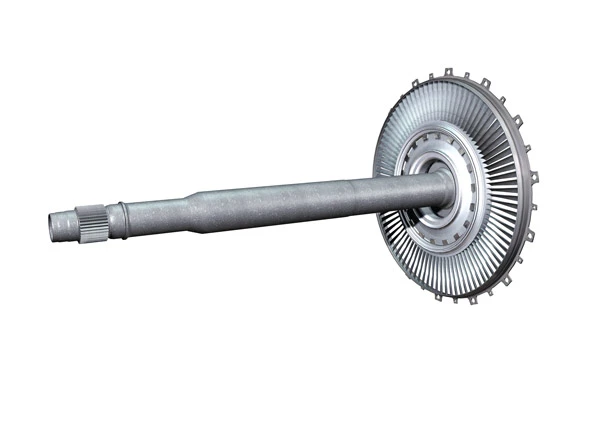

Low-pressure compressor

High-pressure compressor

High-pressure turbine

Low-pressure turbine

Thrust nozzle

Control and monitoring

Combustor

Afterburner

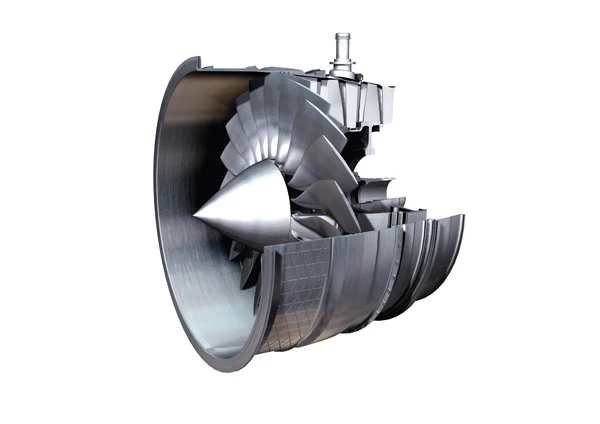

Low-pressure compressor

Low-pressure compressor

The air is compressed in the compressors. The low-pressure compressor (LPC) is significantly smaller than in commercial engines. Unlike commercial engines, pure turbojets have no bypass flow; instead, all the air

flows through the core engine.

Did you know?

The first time blisks (blade integrated disks) were ever used was in the low-pressure compressor for the EJ200.

High-pressure compressor

High-pressure compressor

The air already pre-compressed by the low-pressure compressor is further compressed in the highpressure

compressor. These days, the high-pressure compressor also features blisks, since they enable a higher power density per stage.

Did you know?

The pressure ratio here is generally not as high as in commercial versions, as the air in fighter aircraft is dammed up due to their high speed, for example in supersonic flight. This means that the air is already somewhat compressed when it enters the engine.

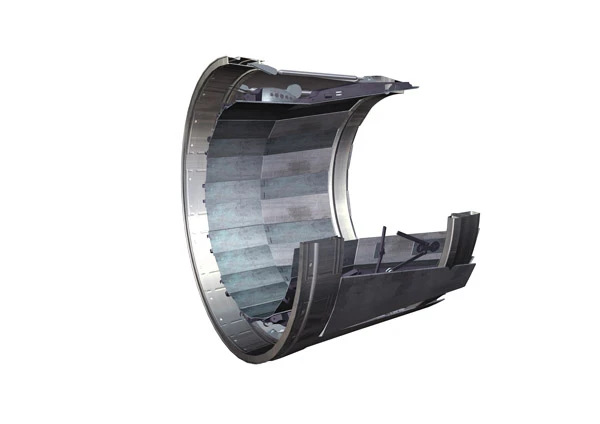

Combustor

Combustor

Here, fuel is injected into the compressed air, which is already at a high temperature, and the mixture is ignited. This unleashes a huge amount of energy, which is used by the turbines.

Did you know?

Because the flame temperature of over 2,000 degrees Celsius is above the melting point of the alloys used, air must be bled from the compressor and blown in for cooling.

High-pressure turbine

High-pressure turbine

The exhaust gas stream drives bladed disks (rotors). The high-pressure turbine sits on the same shaft as the high-pressure compressor and thus provides the necessary momentum for the latter.

Did you know?

The temperature at the inlet of the turbine in the EJ200 is more than 1,500 degrees Celsius, which is why the turbine blades are also cooled with bleed air from the compressors.

Low-pressure turbine

Low-pressure turbine

As with the high-pressure turbine, the low-pressure turbine drives the low-pressure shaft. The combustion

gases then escape from the engine and use their remaining potential to provide thrust.

Did you know?

The EJ200 has a single-stage turbine made of a single-crystal nickel alloy with a ceramic thermal insulation layer.

Afterburner

Afterburner

A special feature of military engines is that fuel can be injected into the remaining air after it exits the turbines and then reburned. This enables a considerable increase in performance and speed in the short term.

Did you know?

In the EJ200, the afterburner can increase thrust by 30 percent.

Thrust nozzle

Thrust nozzle

For optimum engine function and maximum exit velocity, the thrust nozzle at the rear end of the engine

must be variable. The higher the temperature and thus the pressure in the exhaust pipe, the further the

nozzle opens.

Did you know?

In contrast to commercial engines, the thrust nozzle is equipped with an adjustment mechanism to change the outlet diameter.

Control and monitoring

Control and monitoring

All engine processes are monitored and controlled by the engine control unit fully automatically. The broader

range of tasks means military engine control systems must take on more functions than a commercial

control unit.

Did you know?

When firing guided missiles, hot exhaust gases can be sucked into the engine. To prevent negative effects, in this situation the control system closes the vanes slightly and opens the nozzle a little. It also switches on the ignition to counteract a possible flameout in the engine.