innovation

Augmented reality applications for the engine business

In its Inno Lab, MTU is using augmented reality (AR) to simplify the steps to take when working on an engine.

11.2020 | author: Thorsten Rienth | 4 mins reading time

author:

Thorsten Rienth

writes as a freelance journalist for AEROREPORT. In addition to the aerospace industry, his technical writing focuses on rail traffic and the transportation industry.

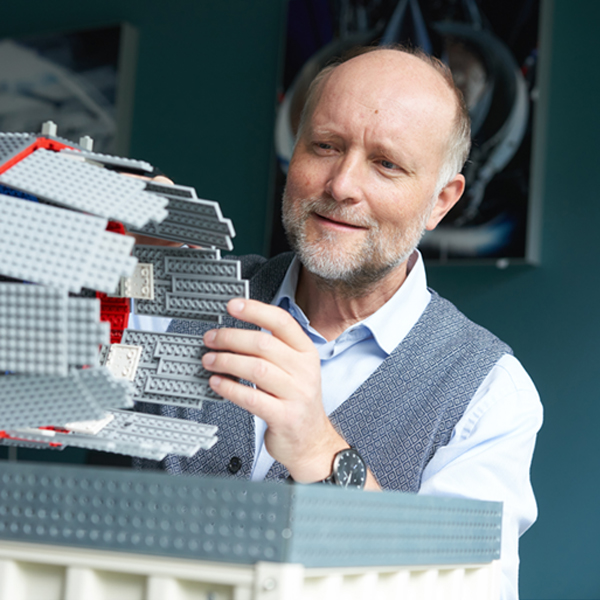

Some things don’t quite fit together as you might expect. On the one hand, the Inno Lab at MTU Aero Engines has a real start-up feel about it with its tall windows and bright, interconnecting rooms. It has social areas and large flat screens, a “pitching” area, a test environment for camera-computer systems and a 3D printer. But then, in another room, you find a Lego® model, and it’s almost like you’ve stepped back in time.

Looks can be deceiving. In fact, the thrust nozzle of an EJ200 engine built out of Lego® bricks is the proverbial gateway to a new world of augmented reality (AR). A world where AR applications could one day provide valuable support for the many work steps involved in the engine business—from component assembly to inspection and quality analysis.

“At the same time, the system could provide automatic access to the corresponding process in the maintenance documentation, for example, to show the mechanic any open repair tasks.”

Proof of concept—and how Lego® bricks fit in

Laying the groundwork for this approach is Thomas Staak, who heads MTU’s Technical Documentation department. He reaches for a tablet and holds it in front of the thrust nozzle model with the camera turned on. A tool appears on the display and a shade opens. Then another tool flashes up. In a stylized movement, it shows how to detach and replace a segment of the thrust nozzle.

The idea is for an engine mechanic to follow these on-screen, augmented reality instructions to execute the work step on a real engine. “At the same time, the system could provide automatic access to the corresponding process in the maintenance documentation, for example, to show the mechanic any open repair tasks,” Staak says. And if necessary, a specialist engineer could support the engine mechanic remotely via the tablet’s camera.

Remote support from far away: Augmented reality (AR) technologies are opening up a world of new opportunities in the engine business. MTU is using AR to simplify work steps.

Embedded in a development project with a specialist Hamburg start-up, Staak and his colleagues have completed the first stage of a long journey. They have a proof of concept—the technical term for the brief demonstration with the camera and model to show that the idea is feasible. Their first task was to test the principle behind this application of AR. The Lego® model of the thrust nozzle let them greatly simplify depiction of the “real” component and build the software based on simple structures. A further advantage of the plastic models is that they are easy to build on—one brick at a time. Every change and every new level of detail is a learning process for the software and engineers alike. “Our colleagues over at the start-up in Hamburg have the same model, which makes it quick and easy for us to jointly tweak and optimize individual functions of the AR application as and when we need,” Staak says.

First AR application in testing: This application verifies that brackets are installed in the right places and correctly aligned. This lets engineers test the bracket mounting process without having to assemble or disassemble real modules.

There is sound, strategic logic behind this approach. “We want to learn how augmented reality works and how we can best apply it to our requirements,” Staak explains. What hardware is useful and what isn’t? How can we integrate artificial intelligence (AI) software, for example to run automated failure analyses?

Test program for first AR application already underway

Anyone who wants to see what Staak means by all this will need to look beyond his section in the Inno Lab. A few buildings further along, in the shop where MTU assembles the PW1100G-JM engine that powers the Airbus A320neo, one of the first tablet-based AR applications has already been tested. Here, too, the development steps were supported by a Lego® model—this time of a Geared Turbofan™, which is considerably larger and more complex than the thrust nozzle. In this application of AR, assistive animations and computer-aided checks are used to verify that small brackets for oil lines on the engine are installed in the right places and are correctly aligned. Thanks to the Lego® model, the engineers can test the bracket mounting process without having to assemble or disassemble real, complex modules. The brackets were 3D printed in plastic especially for the purpose.

The artificial test environment offers another huge advantage. In the assembly shop, day-to-day operations run on a very tight schedule, which leaves no time for any kind of tests or trials. With the LEGO® model, engineers can now check and test the theory for mounting the brackets from the comfort of their office.

However, the test in the PW1100G-JM assembly shop also shows that using AR on such complex components is not always straightforward. “Sometimes an edge reflects, sometimes the light incidence changes and casts a shadow. But we’re getting to grips with that now,” Staak says. And if it’s still not right? “Then we adjust it.” He pauses for effect before continuing: “And that just means we’ve become a little bit smarter, a little bit better.”

Augmented reality and Virtual reality:

Virtual reality (VR) enables users to experience a virtual world in 360 degrees, to view it from every angle, to move around within it and to interact with it. Users feel removed from their actual environment, as if they have been transported into the virtual world.

Augmented reality (AR) meanwhile, simply enriches the real world with virtual content, which means users need to be present where the action is taking place. AR then overlays their perceptions of their real-world environment with real-time information in the form of text and graphics. In contrast to VR, this means AR users remain grounded in physical reality.