innovation

Modular aircraft: Flexibility to save costs

Modular aircraft and cabins allow airlines to respond more quickly to different passenger needs and market situations, making air transport more efficient.

02.2019 | author: Denis Dilba | 9 mins reading time

author:

Denis Dilba

holds a degree in mechatronics, is a graduate of the German School of Journalism, and founded the “Substanz” digital science magazine. He writes articles about a wide variety of technical and business themes.

The transportation of goods in standardized containers, which were invented in 1956 by U.S. transport entrepreneur Malcom McLean, is considered one of the most important developments in logistics. Once loaded into the metal boxes, cargo can be carried over large distances on various modes of transport, including trucks, trains and ships. Grouping cargo in this way does away with time-consuming unloading and reloading and reduces warehousing and laytime costs in ports. This revolutionized goods transportation on land and at sea. Now, Claudio Leonardi from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL) hopes to achieve a similar revolution in air cargo with his Clip-Air concept. The researcher has been working on this futuristic aircraft study since 2009.

Flying-wing aircraft with flexible-use container capsules

Clip-Air consists of two elements: First, there is the flying part: a flying-wing aircraft. And then there are capsules that stack in a similar way to containers on a ship and simply dock to the flying module. Depending on the configuration selected, they can then serve as a cabin or a cargo hold. What makes Clip-Air ingenious is that the capsules can also be used as railcars. “This would effectively let us bring aircraft right into the centers of cities,” says EPFL researcher Leonardi. Passengers would board their “flight” at the train station. The train would then bring the cabin modules to the airport, where they would be coupled to the flying-wing unit. There would be no need for passengers to transfer to the flight or board it separately; they could simply sit back and relax. This would make stress as people rush to their gate a thing of the past, and airports and airlines would also benefit from the time saved. Another advantage of the modular aircraft concept is that operators could respond flexibly to demand, adds Leonardi. “For example, you could attach only second-class or only first-class modules.” Depending on the bookings for a given flight connection, this would avoid flying with an empty first-class cabin, which is a waste of space and of fuel. It would also represent an innovation in rail transport, enabling freight and passenger modules to be transported at the same time.

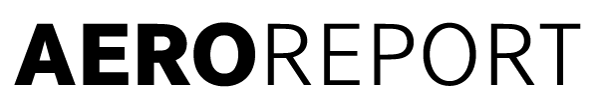

The EPFL scientists have calculated that with a wingspan of 60 meters, the aircraft would have a range of up to 4,000 kilometers. Under the main wing structure, it could carry three modules measuring about 30 meters in length and four meters in diameter—each of which corresponds roughly to an Airbus A320 in size. This offers space to carry either three sets of 150 passengers or a large volume of cargo. Replacing one of the three cargo modules with an additional, mobile fuel tank would also increase the range of Clip-Air, says Leonardi, which is an added bonus. If and when the concept will become reality, however, is still very much an open question. Leonardi hopes, of course, that Clip-Air will take off one day, but he understands that the project is a long-term endeavor.

Coupling poses a technical challenge

Kay Plötner, Head of Economics and Transportation at the Bauhaus Luftfahrt research institute, doubts whether such a modular aircraft concept will ever get off the ground. And the scientist knows the subject matter well: In 2013, collaborating with design students from the University of Glasgow, he and his Bauhaus Luftfahrt colleagues also developed a modular aircraft study that combined rail and air transport.

“Where such systems often fall down is that the aircraft themselves become too heavy and inefficient,” says Plötner. The coupling mechanism for the modules has to be designed in such a way as to be secure. As the forces are concentrated on a few points, a more solid design is required, which ultimately adds more weight. Another complication is that the complexity at airports would increase unless the infrastructure undergoes significant overhaul. “This means you’d have to make very costly alterations to airports and in some cases to train stations as well.” These problems also apply to the current Link & Fly concept from the French technology consulting company Akka Technologies, which involves coupling just one train module with a flying module.

The Bauhaus Luftfahrt expert reckons that the modular Transpose concept from the Airbus research unit A3 based in Silicon Valley has a somewhat greater chance of success. At the start of 2017, the team led by project director Jason Chua presented a concept for modular aircraft cabins.

Clip-Air aircraft compared to conventional commercial aircraft

Flexible aircraft The individual modules are docked under the main wing structure of a flying-wing aircraft. It can fit up to three modules—each of which corresponds roughly to the size of an Airbus A320.

Adaptable cells

These mobile modules are designed to be switched in and out at airports within a matter of minutes, which would allow airlines to adapt their aircraft to the individual needs of passengers on certain routes in the future. According to A3, between ten and 14 of these cabin compartments would fit inside an A330. Chua’s idea is to have modules containing facilities like kids’ play areas and childcare for families, flying conference rooms, gyms and cafés. “This added value for customers should, of course, be an incentive for them to pay a little extra,” says Plötner. Something similar existed once in the past: special modules were designed for the lower deck of the Airbus A340-600. These modules housed the restrooms for economy class, the main kitchen and a relaxation room for flight attendants—albeit at the expense of the usable cargo space. Moreover, they were permanently installed and not exchangeable, as they are in the A3 concept. “Theoretically, the Airbus idea would be feasible,” says Plötner.

Versatile The Clip-Air concept is based on interchangeable modules of different sizes for carrying freight, passengers or fuel, depending on demand.

Versatile The Clip-Air concept is based on interchangeable modules of different sizes for carrying freight, passengers or fuel, depending on demand.

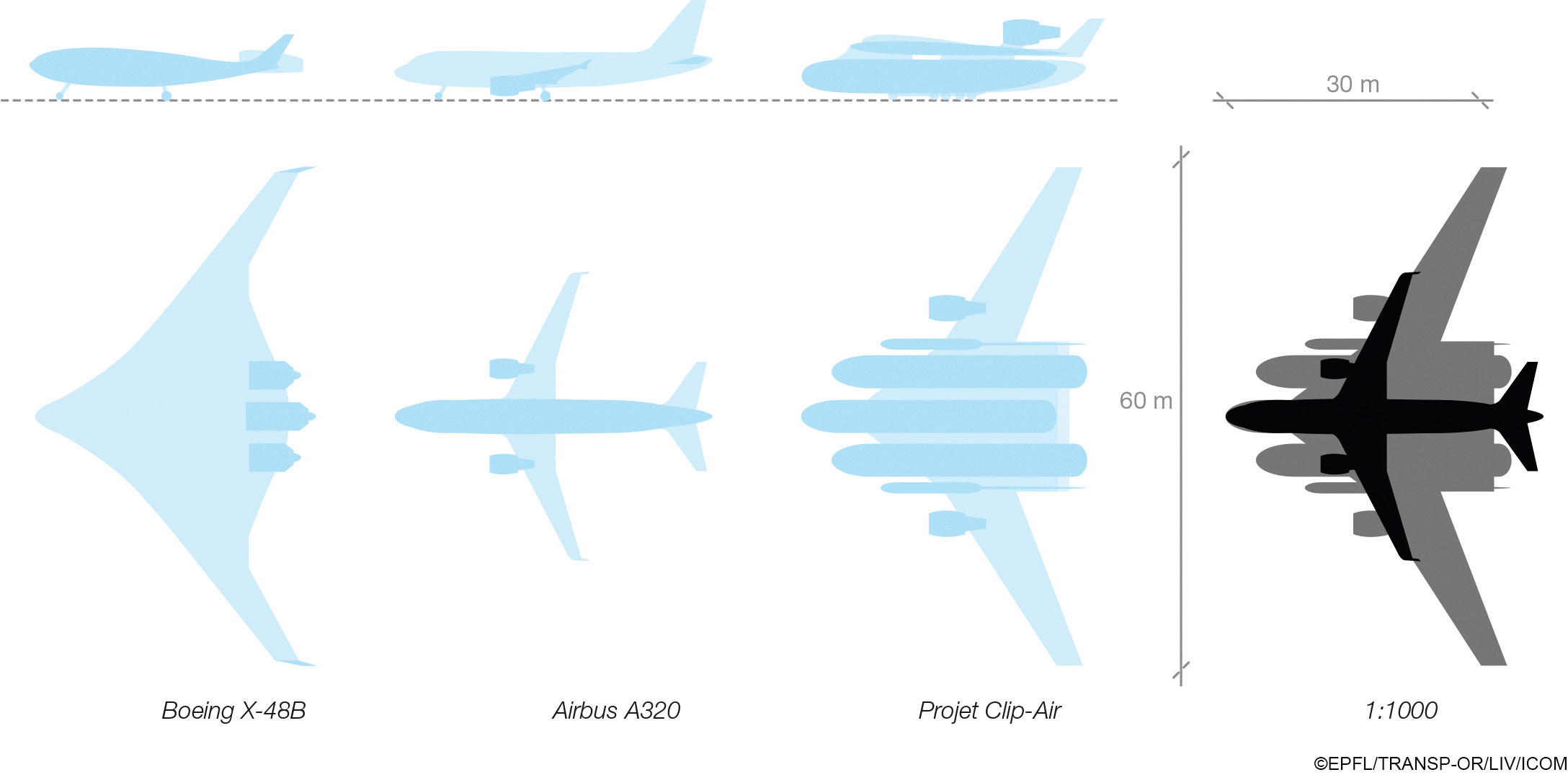

Travel in comfort Clip-Air’s passenger modules can be transferred straight from the airfield to the train station while passengers sit back and relax.

Travel in comfort Clip-Air’s passenger modules can be transferred straight from the airfield to the train station while passengers sit back and relax.

Aircraft from a pool

Whether the demand is there and the modular cabins guarantee higher or at least the same revenue, however, is something that Plötner and other experts are doubtful about. In addition, the airlines would have to carry out new weight calculations for each new configuration of the cabin. Chua is confident nonetheless that a Transpose prototype will take off in just a few years’ time. A3 is already in contact with the Federal Aviation Administration regarding approval, he adds. Plötner and his colleagues are more optimistic about an idea that also takes into account the upcoming individualization trend in air transport, but does not rely on modular concepts: “My response to the demand for flexibility in the future is to have a large pool of aircraft with different configurations available at an airport, so the airline can simply decide based on their booking situation which one they want to use,” says the expert. “We call this an aircraft sharing model.” In this scenario, the aircraft would no longer belong to the airlines, but to a large leasing company, for example.

“We believe this model would involve relatively little alteration to the transport system—you wouldn’t have to make any major changes to the jets or the airports,” says Plötner. The only radical thing about this is the way it changes planning, operations and crew scheduling for the aircraft serving in the network. If all airlines worldwide agreed to take part and, for example, all Boeing 737 aircraft and Airbus A320 jets were combined in one sharing pool, the Bauhaus Luftfahrt researchers calculate that between 20 and 25 percent fewer aircraft would be required. “This would leave transport capacity unchanged but open the door to lower operating costs,” says Plötner. In addition, the global aircraft sharing model largely avoids the costly transition to modular hardware. “Wherever possible, we use things that can be changed via software: light, digital labels and displays.” So, in the same way you install an app on a smartphone, in the future you might be able to switch a leased aircraft from Lufthansa to easyJet with the simple tap of a button.