aviation

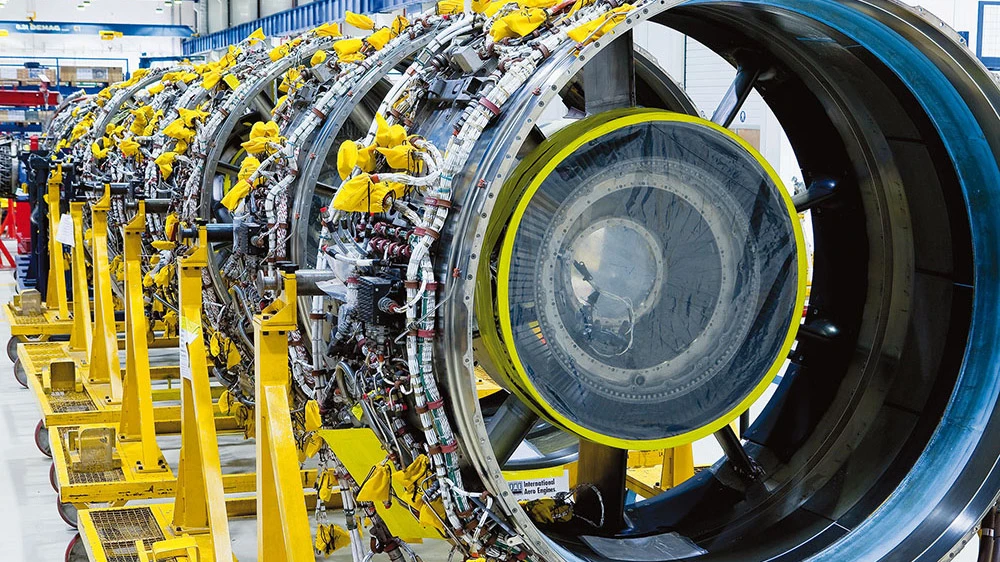

Optimized engine maintenance

Engines are valuable capital assets. That’s why billions of U.S. dollars are invested in maintenance and repairs every year. And this figure continues to rise: engine maintenance is becoming a growth market thanks to the increase in air traffic and new digital technologies.

author: Monika Weiner | 11 mins reading time published on: 01.05.2017

author:

Monika Weiner

has been working as a science journalist since 1985. A geology graduate, she is especially interested in new developments in research and technology, and in their impact on society.

Too old to fly? Engines only get older. “From a technological point of view there is no age limit,” says Leo Koppers, Senior Vice President Marketing and Sales at MTU. “We see it with the V2500. Some of these engines are almost 30 years old now and still fully functional.”

However this requires some work, as engines are, of course, subject to wear and tear in flight. Maintenance intervals are dictated by strict safety regulations, and the components also wear more quickly depending on where the engine is used: in 2015 almost 30 billion U.S. dollars were spent worldwide on engine maintenance, repair and overhaul, or MRO for short. For 2025, the forecast is 46 billion U.S. dollars. That is a lot of money for airlines feeling the cost pressure from intense competition. The question as to why it is still worth their while investing increasingly high sums to make their engines last forever, or at least for a long time, is one that Dr. Andreas Sizmann, Future Technologies and Ecology of Aviation expert at Bauhaus Luftfahrt, has the answer to. “First and foremost, airlines want to secure the availability of their fleets, because any downtime is associated with high losses. At the same time, they’re pursuing the goal of keeping maintenance costs as low as possible.”

All aircraft owners have different requirements

The amount an aircraft owner is willing to spend depends on many factors. First there are external constraints, such as maintenance intervals that are required by law and must be complied with. However another important factor is the age of the engines, and whether the aircraft are the property of the airline and are set to remain so over the long term, or whether they are leased. With owned aircraft, the airline itself can determine the time-scales for flight operations. Leasing companies that are interested in retaining the value of their aircraft may demand specific maintenance work and closer maintenance intervals. The conclusion to be drawn from this is that the market is huge, but every customer is different.

And there are considerable differences among MRO service providers, too: on the one hand there are the original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), including e.g. GE Aviation, Rolls-Royce and Pratt & Whitney. The original parts they offer are expensive, but these improve value retention. This is an important criterion for owners who want to resell their aircraft ten to fifteen years down the line. Yet a range of comprehensive services is also offered by independent suppliers such as MTU Maintenance, who are able to install original parts but do not necessarily have to. However, all MRO service providers have things in common: they are continuously developing new technologies that allow maintenance work to be optimized and—for jobs that cannot be avoided—completed in the quickest possible time.

“One promising approach is electronic engine monitoring,” explains Koppers. “There are dozens of sensors taking in-flight measurements of exhaust gas and engine temperature, fuel and oil consumption, vibrations, and the pressure in the compressor, combustion chamber and turbines. The data can be read out after the flight or sent via satellite from the on-board computer to the ground station and instantly evaluated there. This allows us to detect technical problems early on, plus it enables us to better plan any necessary maintenance work.” In this way, the shop visits can be adapted to actual requirements. If an engine is mainly used in desert regions, for instance, where there is a lot of sand and dust in the air, it has to be sent to the engine shop sooner than an engine operating in northern Europe or North America.

Inside view Two employees at MTU Maintenance Hannover carry out a borescope inspection of a V2500 engine.

Increasingly long on-wing times

“Overall the trend is moving towards ever longer maintenance cycles,” emphasizes Koppers. “This is down to both improved monitoring and increasingly reliable technology. While the V2500 required up to five shop visits over its lifecycle, new NextGeneration engines like the PW1100G-JM or the LEAP will be able to make do with three, based on current trends.” And fewer shop visits mean less downtime and lower costs: for a full service, the engine has to be removed and a replacement engine installed, which takes at least eight hours. In the meantime the engine to be overhauled is brought by aircraft to the engine shop. Mechanics are on hand to clean, test and, if necessary, replace the components (see How an engine is maintained). That can take weeks and costs millions in high-quality materials and spare parts. What’s more, much of this complex work is not only technologically challenging, it is pure manual work. So any shop visit saved or postponed is a win.

Of course, such visits cannot be delayed arbitrarily: because single components like blades and sealing segments are subject to extreme loads, the engine’s performance decreases over the course of time. As its level of efficiency drops, the combustion temperature and fuel consumption increase, which is noticeable by the higher exhaust gas temperature (EGT). The drop in the difference between the permitted maximum temperature and the temperature in flight, the EGT margin, demonstrates the need for and success of maintenance work. In order to bring the EGT margin—and with it the engine’s efficiency—back up, a shop visit must reduce the clearance between the blade and the abradable lining in the high-pressure turbine, for example. To achieve this, linings are fitted to the inside of the casing, or a layer of hardfacing material is soldered onto the blade tips.

Cost optimization for older engines

The first shop visits may be expensive, but costs really jump once an aircraft reaches the end of its life after 25 to 30 years. That’s why MRO providers such as MTU Maintenance offer a whole range of mature engine service solutions to avoid the costs of maintenance that is no longer worthwhile: repairs, installation of new or used spare parts, disassembly and recycling, or the leasing of replacement engines. It is up to the customer.

“The really crucial factor here, though, is not how we make short-term savings but rather how we achieve long-term success,” stresses Koppers. “At MTU Maintenance we’ve developed a lifecycle optimization concept that encompasses maintenance economy, value retention and customer satisfaction. We try to find the best solution in each individual case.” So for an engine that has a planned time on wing of ten years, the recommendation would be to install original parts, whereas for an engine that still has a few thousand take-offs and landings ahead of it, used and repaired spare parts may well be sufficient. “The advantage we have as an independent provider is that we can offer original spare parts, but we’re not obliged to. At the same time we also help the customer ensure that the engine is ready for operation whenever it’s needed, and that it can be sold at the best possible price in the end.”

Future trends

Yet in spite of all the optimization strategies being implemented, billions are still being plowed into maintenance; in recent years, the costs of shop visits have even gone up because engines are becoming more and more complex. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), engine maintenance costs made up 42 percent of total maintenance costs in 2007, but in 2016 this figure had already reached the 50 percent mark.

One thing Bauhaus Luftfahrt researcher Sizmann is sure of: “The cost pressure that airlines are facing will bring forward new testing and analysis procedures. And these will help ensure that engines have a longer time on wing in future, and that a lot of the work can be done directly at the airport during normal downtimes.” The engine OEMs are already adjusting to this change, says Koppers: “The avoidance of maintenance costs is already built into the engine development process, for example by using modular designs that allow entire units to be replaced, thus simplifying repair work.”

You may also be interested in following content

Fly-by-hour or time-and-material agreement?

Shop visits are expensive. Engine maintenance and repairs are a significant cost factor for airlines. That’s why maintenance companies offer a variety of service models to help customers keep track of costs.

“Virtual technologies will also help save time and cut costs in the future,” Sizmann predicts. “For example, we are currently exploring the potential that big data analysis offers. Improving the recording and evaluating of the condition of an engine during normal operation with the help of a deeply integrated network of sensors, without having to remove and dismantle it, could reduce costs. Augmented reality, meaning computer aided extension of reality perception, also offers interesting options. Computer-generated additional information on displays or smart glasses is already employed in some areas of construction or maintenance. There is yet potential to exploit.” He also believes that additive manufacturing with 3D printers which could help manufacture spare parts near-wing, without complex storing and logistics, is another field that shows promise.

A lot of this is still pie in the sky, but who knows: maybe the maintenance, repair and overhaul of engines really will be so easy, quick and flexible that it can be done at any airport.