aviation

The Transall flies off into the sunset

The Transall has been faithfully serving the German Air Force for over 50 years. But its story will conclude at the end of this year—and with it MTU’s work on the Tyne engine.

author: Thorsten Rienth | 5 mins reading time published on: 07.07.2021

author:

Thorsten Rienth

writes as a freelance journalist for AEROREPORT. In addition to the aerospace industry, his technical writing focuses on rail traffic and the transportation industry.

Christian Knoll has seen a great many things since joining MTU Aero Engines in the late 1970s to train as an engine mechanic. But standing under the 5.45-meter propeller, he giggles excitedly like a little boy who has just got his hands on his first slot car racing set. But instead of the controller for a race car, he’s holding two propeller blades. In combination with two Tyne engines, they once provided thrust for a Transall C-160D—the all-round cargo aircraft that for half a century helped shape not only European aviation history but also Knoll’s life story.

Tyne and Transall have been central characters in his life all these years. At the beginning of his career, Knoll worked on the engines themselves; now he is part of MTU’s technical customer support team. His opposite number is Thorsten Schrader of Air Transport Wing 63 at NATO’s Hohn Air Base in northern Germany. As Sergeant Major and expert validator in the engine inspection group, Schrader is the last one to sign off before an overhauled Tyne engine is allowed to return to the skies.

Enough space for a Puma helicopter

Measuring 32 meters in length, the Transall C-160D possesses the power to take off from a 730-meter runway and reach its maximum operating altitude of 8,000 meters. Even when carrying a load of 14 metric tons, it can cover a range of 1,200 kilometers at a speed of 455 kilometers per hour. Its hold is even large enough to accommodate a Puma helicopter.

The Transall also features an upswept tail assembly, which allows freight to be loaded, unloaded and—depending on the mission—even dropped while airborne via a large ramp at the rear. Its twin-tire front landing gear can be rotated up to 55 degrees in either direction. In combination with the aircraft’s thrust reverser, this allows pilots like Lieutenant Colonel Tino Müller to turn the transporter on standard-width runways.

Knight in shining armor, or angel of the air

Since he first took position in the cockpit 18 years ago, Müller has logged more than 3,400 flight hours. “The Transall is a very amenable, very safe aircraft,” Müller says. “But it’s also incredibly versatile.” This is mainly due to its service history. Originally designed as a military transporter to be deployed in war zones—which explains the bulletproof floor of its cockpit and front hold—the Transall’s main role became that of knight in shining armor.

Missions during the famines in Ethiopia, the Manjil–Rudbar earthquake in northern Iran and as a pillar of airlift operations during the siege of Sarajevo earned the aircraft the name “angel of the air.” It was for Sarajevo, which sits in a deep basin and was being bombarded from all sides, that the aircraft’s crew developed a custom descent technique that sees the Transall leave its safe altitude only at the last possible moment and at an extremely steep angle of descent.

It can angle its nose downwards by six degrees. “That’s twice as steep as any other aircraft,” Müller says. Meanwhile, the pilots extend the flaps at 60 degrees, which means that instead of just delivering lift, they also offer substantial air resistance. These are further aided by the air brakes. “They ensure that we’re still traveling slowly enough to avoid putting too much strain on the airframe,” Müller explains.

Not many other pilots will equal his 3,400 flight hours, because the Transall’s fate is sealed: at the end of 2021, after more than five decades of service, It’s time to sound Taps.

“Like a big family that sticks together.”

Sergeant Major Schrader from the inspection group would rather not have to think about it. Even hardened servicemen like him melt when it comes to retiring the Transall. “I was there when a set of hydraulic pincers arrived to dismantle a Transall,” he says. “Many of us feel we’re losing a part of ourselves, it’s heartbreaking.” The peace and quiet he will enjoy at home after the Transall is retired is little compensation. He lives just 17 kilometers from Hohn Air Base. “We can hear that pleasant, low hum every time the aircraft do their rounds.”

Thanks to the “mumbling bee,” Schrader has seen almost every corner of the world. In it he has flown food to Ethiopia and performed a medevac mission from Australia to East Timor. Together, they have brought disaster aid to Central America, supervised low-altitude exercises in northern Canada and spent several months in Afghanistan.

Yes, Afghanistan. “Once, during a routine valve replacement, we pulled not only the valve out of the engine, but also a piece of conduit.” This had never happened before, either at Hohn or anywhere else. “We didn’t quite know what to think. Was that just a piece of piping, or had the other end of it been attached to a flange that had now also been dislodged?

Schrader had the cell phone number of Knoll’s predecessor at MTU technical support. “It was Friday afternoon when I called him, and he was out sailing on Lake Starnberg in the south of Germany,” Schrader says. From the boat, he made a quick call to the test stand team back at MTU. “He then called me back and said ‘No problem, we’re putting together a repair kit for you, complete with specialized tools and assembly instructions’.” The kit was rushed on the next transport bound for the Hindu Kush. Once Transall, always Transall. “Like a big family that sticks together.”

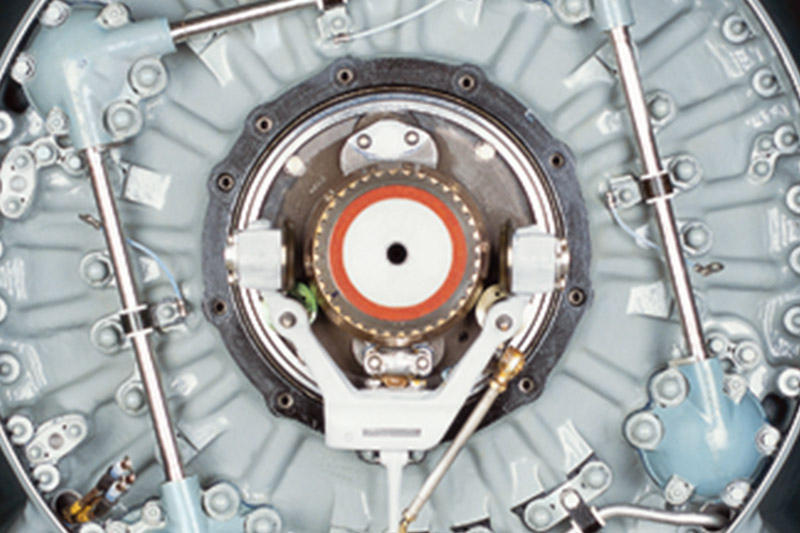

The Transall engine: Until delivery of the TP400-D6, the powerplant for the Airbus A400M, the Tyne was the most powerful propeller engine in the Western world.

The Tyne engine

The Tyne engine

Until the arrival of the TP400-D6, which powers the Airbus A400M, the Tyne was the most powerful propeller engine in the Western world.

Featuring a planetary gear train comprising propeller and compressor, this twin-shaft engine had clocked up 2.172 million flight hours by the end of 2020.

Between 1965 and 1972, MTU assembled 470 Mk 22 engines as part of a Rolls-Royce license for the Transall. These were joined by 315 Mk 21 parts kits for the Breguet Atlantic maritime reconnaissance aircraft. MTU’s focus then shifted to maintaining Tyne engines and manufacturing spare parts.

It is through engines like the Tyne that MTU gradually got itself on an equal footing with international engine manufacturers

“What the operators of Tyne engines valued most of all was their unbelievable robustness,” Knoll says. “They feature parts that last for ages. Just because a couple of drops of oil are leaking out doesn’t necessarily mean the engine has to be immediately shut down.” And if it does? “Then the problem can usually be found right away and dealt with in no time.”

According to Knoll, the Tyne engine has 928 MTU modifications to its name. “For MTU, the Tyne was a constant test subject, one that flew in really harsh conditions such as ‘hot and high’ and ‘sand and dust.’ We’d hit the jackpot!” MTU also completed 73 development and improvement programs. “Definitely one of the most extensive programs concerned water/methanol injection for additional thrust.”

But Knoll sees a different aspect as being much more important. “Through military license programs like those for the Tyne, J79 and T64, MTU gradually got itself on an equal footing with international engine manufacturers.” In turn, this opened the door to participation in consortium developments such as the RB199 (Panavia Tornado), MTR390 (Eurocopter Tiger), EJ200 (Eurofighter Typhoon) and TP400-D6 (Airbus A400M).

In September, the Tyne master engine will be switched on for its final full correlation run—almost 55 years after the official acceptance test, which took place on the test stand formerly operated by MTU’s predecessor MAN Turbo on November 18, 1966.

As the curtain rises for the new year, it will fall for the Tyne—bringing a memorable era to an end. Anyone wishing to jog those memories can take a wander through the open-air part of the MTU Museum, where a Transall propeller has been on display since spring 2020. Serial number: D-103; tactical number: 50+66; entry into service: April 16, 1971. It was restored by members of “Friends of MTU Engine Technology.” And the man who organized all this was, of course, Christian Knoll.